all of the selves we Have ever been

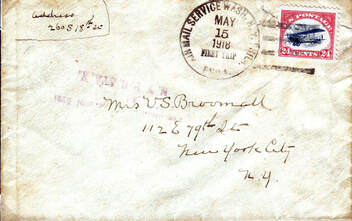

I have always loved getting the mail. Real mail. Paper mail delivered by the U. S. Postal Service. In years past, opening a mailbox filled to bursting was like striking gold in the Yukon. That level of excitement cannot be compared to the nauseating feeling of opening your email inbox today and seeing 200 new messages. As a little girl, I lived on-and-off in a small town where there was no door-to-door delivery. Citizens walked to the post office to collect their mail from a small, square box inside the main post office building. There were no keys to these mailboxes. Patrons had to remember the combinations. As I moved ahead in grade school, I was sometimes sent to the post office to fetch the mail. To a seven year old that was the equivalent of being named a diplomat. In our family’s diplomatic corps, I had a father serving overseas, and we sometimes received letters from him in special air mail envelopes with red, white and blue borders. International mail in a small town was a big deal. As my father’s image grew hazier in my young mind, the letters he sent reminded me that he was real and still out there somewhere. Sometimes my older sister and I would fight over who got to do the honors of getting the mail. It was always dangerous if we walked to the post office together without having worked out the details in advance. Truth be told, each of us walked along plotting how to get to the box first and apply the combination that would open the little door to the mailbox. There were times when my sister and I got into arguments about this while at the post office. This was dangerous. In a small town where everyone knows your name, someone was going to call your parents and maybe your grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins as well. That could get a girl kicked off of the honor detail. Skirmishes aside, I never lost my love of getting the mail. In later years after we relocated to a suburban neighborhood, we grew accustomed to the rhythms of our daily mail carrier. We would kneel on the couch and watch for him through the bay window. The mailbox lined up directly with the middle cushion of the couch. As soon as we saw the mailman, we zoomed outside for the mail. If we saw the mailman getting out of his truck, we knew there was really big news—maybe a certified or registered letter or a package too big for the mailbox. Of course, there was rarely mail for children back then. The fact that it was rare but it DID happen made us all the more faithful to mail-watch duty. Ah, the power of intermittent reinforcement!! For me as child, mail might be a birthday card. My Aunt Lillie faithfully sent each of her nieces and nephews a birthday card containing one dollar for each year of life. It was especially exciting when we crossed into the double digits— to 10 and beyond! The other exciting mail came from my paternal grandmother who lived in New York City. She was quite the seamstress, and she would send the most beautiful handmade clothes for our Barbie dolls—it was like a shipment from the House of Chanel—teeny tiny haute couture. By the time we were further along in grade school, the mail included subscriptions to Highlights for Children. Thus began my love of magazines. Over the years, we also enjoyed the magazines our parents received--National Geographic, Life, Look, Good Housekeeping, Readers Digest, and Redbook. Back then, magazines were loaded with content, pictures and coupons too. Another special assignment of childhood was to clip those coupons. Catalogs came in the mail in an abundant supply. We didn’t shop a lot back then. You got new things on special occasions or at the start of a school year or season. But that didn’t stop us from dreaming. We wore out the pages, marking items with pens and pencils, dog-earring the corners, and coming back to certain pages over and over again. There were catalogs for every product imaginable. If someone in the household did make a purchase then that led to a flood of new catalogs arriving in the mailbox in the days following. Those catalogs allowed us the joy of hope, longing, and occasionally, the anticipation of an order that was coming not overnight, but “any day.” High school brought new types of mail. We were inundated with flyers and brochures from colleges and trade schools. Our personal magazine subscriptions included Teen, Glamour, or Seventeen. Friends on vacation might send postcards, and now, in addition to birthday cards, there were graduation announcements and cards. By the time we were young adults, the junk mail had our names on it. And the bills were addressed to us too. Some good things still arrived like birthday cards, letters from friends, income tax refunds, our own magazines like Self and Runners World, and an assortment of catalogs. We received personalized Christmas cards and not just the one addressed to “the family of.” As I and my friends married and had children, there were bridal shower invitations, wedding and birth announcements. I received a letter from one dear friend that her mother had died and news from another that her husband had passed away in his sleep. In the current times, my young adult children check their mail maybe once a week. While younger people may have packages arriving daily, they are not invested in the paper mail like those of us from earlier generations. During this time of shelter- in-place, I find myself returning to that time in my youth when I memorized the rhythms of my mail carrier. I can hear the purr of the mail truck’s engine a mile down the road—and that is in urban traffic. I watch from the window as his truck arrives. I know about how long to wait before checking my mailbox. Most days, I find the mailbox empty. So much is done online. I sort through the occasional junk mail, store flyers and coupons. But it is always a joy to find something personal. Getting mail is a reminder that your people are out there somewhere, and that they still care about you and are thinking of you too. They went to some effort to create, stamp and mail this item to you. Seeing the familiar handwriting of someone you love is like catching the scent of someone familiar when you are lonely and least expecting their presence. The return address physically brings another part of the country or the world into our hands even as we cannot leave our homes. In my house there is a box filled with treasures that once came in the mail—letters and greeting cards saved from friends and family, people both present and long gone. They are special reminders that renew old relationships and memories. The familiar handwriting and the sometimes corny messages bring them back to me. Each saved letter or card is not just a piece of mail, it is a snapshot of my history and piece of someone loved. I cannot imagine a time when I will wait a week to check the mailbox. Especially not now. I know I will never outgrow the joy of getting the mail.

0 Comments

I find myself more sentimental than usual during this quiet time of shelter-in-place. Can you identify the correct decade for these favorite toys, new foods, popular actors, and chart-topping songs:

Have fun! Answers on Friday.  It is Easter morning 2020. As I shelter in place, I have plenty of time to reflect on the question, what is church? Surely, it is more than legality. Church happens in places where people have no enforceable first amendment rights. Church lives in places too poor for cathedrals. It exists in places too dangerous to gather, places where militias roam the streets looking to take whatever you have, your life included. What is church? My earliest personal memories of church begin with my maternal grandmother, my Sita. She was a deeply religious, devout servant of the Lord. My humble immigrant grandmother was so full of faith she glowed! Watching Sita could turn a person into a believer; I know it worked on me. Sita walked from her home to church every day. On school days, I would see her from the adjacent school playground. Even as a first grader, my Sita’s devotion moved me enough to stop what I was doing to watch her pass. I saw a living example of faith. In Sita’s house there were many religious symbols. I often saw the black beads of a rosary entwined in her work-swollen fingers. On the wall of her sun porch hung a copy of the famous painting of the sacred heart of Jesus, the one with the eyes that seemed to follow you. Sita had Jesus watching us every time we entered or departed from her home. On a mantle there was a statue of the Virgin Mary that reigned over the living room. My father did not grow up Catholic, but he converted before marrying my mom. That was how things were done back then. I know dad did it for mom, but I believe he fell under Sita’s spell and did it for her as well. On the day my father left for military duty in Pakistan, there was quite a scene at Sita’s front door. The extended family gathered to say good bye. Pakistan was far away, poor, mysterious, and dangerous at the time. It is difficult today to appreciate the time before cell phones and internet. It was an era when landlines were new and international telephone calls difficult. Postal mail was slow. It was hard for families to be that far apart for so long with no word. In the midst of the farewell, Sita took the statue of the Virgin Mary from the mantle. She brought it to my dad at the door. As dad stood there in his dress blues, Sita insisted that my father kiss the statue of Jesus’s mother. I saw tears well in my dad’s eyes, and he followed Sita’s instructions without protest. And then dad was out the door for what seemed like a very long time protected by both the smooches of his children and that kiss of faith. A few years later, when Sita died, we were living on an Air Force base in California. My mother had flown alone back to Ohio to be with her family. I remember when my father got the call from my mother. He went into our small kitchen and pulled the pocket door so hard that it repeatedly ricocheted back and forth between the sides of the door frame. Realizing something significant was happening, I peeked into the kitchen. I saw my father bent over the sink weeping. It was the only time in my childhood that I saw my father consumed by that kind of emotion. My father sure loved his mother-in-law. Sometimes we sign up and go to church to humor someone else, and then we find that church grows into a space inside of us. We borrow faith until it grows big enough for us to share with others. My Sita’s faith was both a cloak and a seed for her entire family. Church was in session wherever she was. As a child I loved the rituals of church. I enjoyed the pause in the services as the collection plate was passed. I coughed up bits of milk money and allowance to place something into my tiny envelope as a church offering. In my way, I helped to pay for the new building and contributed to social causes. In school we donated money to save orphans and pagan babies around the world. I marched in processions carrying flowers and later candles. I witnessed countless baptisms, communions, confirmations, and funerals. I blessed myself with holy water and genuflected before I took my seat. As I got older, I joined the line of people coming forward to partake of communion. I learned when to stand, to sit, and to kneel. There were fasting and special prayers that gave the ceremonies significance. In my earliest days as a churchgoer, the mass was in Latin. The language difference added mystery and more significance to the service. I thought Latin was the language of God. Later, as missionaries visited our church and gave sermons flavored by accents from the larger world, I learned that God speaks many languages. I also loved the sensory experience of church. There were beautiful stained glass windows, sparkling gold chalices, and shimmering votive candles. There was the cool water on my fingertips as I made the sign of the cross. The smell of incense said it was a holy and special occasion. Later there was the taste of the wafer and the wine. People packed the pews and sat in individual silence until it was time to join together in one voice of prayer and song. There were organs and later pianos, guitars, and violins. As I grew up there were new kinds of services, new towns and new churches. I developed a broader understanding of church and of faith. Much later in my life, church would be at my bedside as I lay in an intensive care unit with one foot in the afterlife. Amid terror, tubes, and machines, a man in a familiar black uniform and white collar stood at my side to offer last rites. Surely, I was at church. There have been plenty of times since then that I have held church in the shower as I prayed for my children. I often hold prayer services in my car as I dodge traffic and aggressive drivers. I’ve prayed with others on front porches and over the telephone. I have been in God’s presence at hospice bedsides and in nursing homes. The lessons of faith I learned while growing up in church were messages that included “love each other” and “feed my people.” Never have these messages been more universal. On Easter Sunday 2020 church attendance is up. It is taking place in ICUs and at food banks. Silent sermons are being shared at grocery stores where people stand six feet apart waiting to enter. Our Easter outfits are colorful face masks and purple latex gloves. Yesterday, a big white Easter bunny drove through town in the back of pick-up truck waving and sharing faith with children, reassuring them that the world is in good hands. It will go on. Perhaps contagion is not just the story of disease. Maybe it is also the story of faith. We catch it from each other. And maybe that is why church is so important to so many. Especially now. But Church is not a building. It can be found anywhere and everywhere that people heed the message. From the church that is in me to the one that is in you, Happy Easter!  The world has changed since we learned of the coronavirus. People are talking about the ways in which life will continue to transform during and after recovery from this pandemic. In the new future, we may not exchange handshakes or hugs. We may be wearing face masks at social gatherings and carrying canteens full of hand sanitizer. While we focus on the rituals that we will leave behind, one blast from the past that I hope makes a comeback is drive-in movie theaters. Remember those? With our concerns about keeping a safe distance and the closing of the retail establishments that took over many of the former drive-in parking lots, it seems like the right time to scale up that delightful form of summer entertainment. Despite DVDs, cable and streaming services, people still like to go to the movies. There is something about seeing a film on the big screen that makes us feel more engaged, like we are in the story too. Many movie theaters are updating to make a more exciting and comfortable movie-going experience. These modernized venues have bars where you can purchase alcoholic beverages and a growing menu of restaurant foods. Some theaters will even serve you in your seat. People also rave about the new chairs---plump, comfy recliners! There is special matinee and senior pricing and movie rewards club memberships to make attending shows more affordable. But is all of this really new? The drive-in had this all covered beginning way back in the 1950s. A trip to the drive-in was no casual matter. It involved a certain amount of planning even if on short notice. There was a level of excitement in the preparations that left a child’s heart brimming with joyful anticipation. No complaining about the seat selection. You brought your own seat, and you could bring a pillow and a blanket too. The screen was as big as a building. And each car had its own speaker, so you were in charge of the volume. You could have some control over the people who talk and make noise during the movie. No kid with a brain wanted to be ejected from his or her seat and have to sit outside on the gravel! If you chose to separate yourself, you could always bring a lawn chair and stretch out alongside the car. If the movie proved to be too long or a big dud, there was usually a play area, a snack bar, restroom, or a neighboring car full of kids as restless you. You could leave your seat and move around in small groups without causing a scene. There were no rules against bringing your own snacks. If you wanted a full meal, you could bring a feast in a cooler. There was no need to mortgage the house to pay for snacks for a family of six or eight. You could bring a full bar if you wanted as long as your behavior didn’t get out of hand. The theater manager didn’t know and didn’t care. Your auto was your ticket, one small fee per car. You could bring as many people as you wanted. Talk about good pricing! And, most exciting of all, you could come in your PJs! That was about as risqué as a seven year old could imagine—going out in public in your pajamas. The drive-in got more salacious for teenagers who came there for a cheap date and making out, but they didn’t usually come in their pajamas. That would have been way too obvious. Some of those old drive-ins had five or six hundred parking spaces. When you multiply the number spaces by the amount of people in each car that is quite a crowd! Will we ever be able to safely gather in those numbers again? Maybe we can. At the drive-in.  I am trying to establish a daily routine, stick to a plan. My mind does not want to cooperate. It may have gone AWOL. My normally busy, creative brain is at a standstill. Usually full of questions and ideas, my head is now as empty as a jack-o-lantern. I open a window to the outside world and enjoy the incoming breeze. I order my mind to give me some sign of life My thoughts drift to a man I once met, a Holocaust survivor. He was a small boy about the age of five when the Nazis overtook his country. He witnessed so many horrors. His youth was spent surviving, surviving the terror as family members were shot and raped in front of him. He survived the ghettos and a youth spent on the run and in hiding. Fear and starvation were his constant companions. By the time the war was over, the boy was a teenager. As he waited in a new kind of camp to be re-settled, the boy liked to wander the streets of town looking in windows. He enjoyed watching people work and shopkeepers waiting on customers. He relished the sights of families gathering for meals, or groups of heads bowed in prayer, men reading newspapers, and mothers embracing their children. You would think a youngster who had witnessed so much horror would have lost his innocence along with his youth, but this man retained a sweet, childlike craving. He told me that when the war ended, he was left “so hungry for people.” He looked into the windows as a student of life, trying to understand how people were meant to live. What he saw filled him with hope and joy and determination. I think of this man often. He and his stories give me courage, hope and perspective. As I think of him today, I realize that my head is not empty, but that I, too, am hungry for people. While my situation in no way compares to what this man went through in war, the current isolation leaves me with a yearning for others and the shared way in which we once lived. Technology has been a godsend during this pandemic, but smartphones, tablets, and computers are not enough. The current that runs through our devices pales to the surge of electricity that runs through us when we pray aloud together, share a big meal, or do productive work side-by-side. Facetime with the grandchildren is a technological miracle, but it is no substitute for cuddling them in our arms. The feeling of delight and anticipation when preparing Sunday dinner for a gathering family cannot be compared to even the most delicious take-out order. The infusion of learning, the lights that come on inside us when we stand beside a talented colleague and watch them work is far more exhilarating than a YouTube video. Man was not meant to live alone. When the Creator saw that man was lonely, He gave him a partner. Together the man and his partner created the family of man. When we are together, we share the warmth of the divine spark that it is in each of us. That is a heat that cannot be reproduced by technology. Right now I feel like the world is in a universal time-out. Perhaps we all have been sent to our rooms to think about what we have done. We have orders not to come out until we learn how to get along. In many sectors, it seems to be working. I plead to be let out. I promise to behave, to do better, and besides, I’m starving. My head is not empty. It is hungry. Hungry for people.  Most of us never imagined that we would be called upon to help save the world. Saving the word is the work of superheroes in distinctive, trademarked costumes, of servicemen and women in camouflage, or first responders wearing helmets and holsters. But there are no uniforms or badges for this call of duty. We do not fight fire with fire. We fight tiny with tiny. A microscopic organism has set the world aflame. Now, it is all about the significance of small things. The things we once took for granted are now our strongest weapons. Small acts of kindness are the droplets joining to become the rushing force of water through a fire hose. We de-rail the movement of the enemy by keeping our hands from our faces, washing those hands, and staying home. Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation has become a short phone call to a lonely neighbor, a call that can be lifesaving. We understand rationing and are grateful for small amounts—a couple of bucks set aside in the cookie jar, a few rolls of toilet paper in the closet, a palm-sized bottle of hand-sanitizer in a purse, a single, old bandanna covering a mouth. Though all of my needs are met, I admit to moments of battle fatigue. In those twitchy moments of impatience, I reflect on the past world wars and remember the veterans and Holocaust survivors I have known. They remind me that the world is not saved by superheroes, and small is not the opposite of greatness. Their lives and history tell me that greatness is the result of small—the accumulation of small acts carried out by masses of ordinary people who dug deep and stayed the course. So, today, despite my weariness, I re-commit to do my part one day at a time. I will join the war effort like they did—because it is the right thing to do. And I will do it for them because they saved the world for me.  When I was growing up, each day of the week had a certain structure. The Monday through Friday routines were so similar that they blended into what seemed like one long day, especially during the school year. The weekend was different. Saturday and Sunday each had a unique rhythm and mood. Hands down, Saturday was the best day of the week. It was like a mini-summer vacation in a 24 hour period. Saturday really began late on Friday afternoon as soon as the school doors slammed shut behind us. Done with classes for the week, we could stay up late and maybe even have a few friends over for a pajama party. Saturday morning was a glimpse of paradise. Everyone was relaxed and happy. No parental supervision was needed. Mom got up early and went for her regular appointment at the beauty shop. Dad grabbed his coffee and cigarettes and headed down to his workshop in the basement. I and my siblings slept in. There was no need for alarm clocks or pleading parents. Once awake, we lounged in our PJs watching cartoons until noon. There was no official Saturday breakfast. We grazed on cereal and Nestles Quick while parked in front of the television set. We sprang to life on Saturdays when mom pulled into the driveway. Following her appointment with the hairdresser, she did the grocery shopping for the week. That was back in the days of bigger families who cooked and ate every meal at home and packed lunches for school. It was also the time when stores closed early in the evening and stayed closed on Sundays. There might be one car to a family. During the week, that car was with dad at work all day. If you didn’t get what you needed from the store on Saturday, you just had to wait a week or borrow from a neighbor. Too much borrowing could lead to a bad reputation in the ‘hood. As a result, the weekly trip to the store resulted in a tractor-trailer-sized load of groceries crammed into the back of a station wagon. We groaned at the sound of the car horn. Getting the groceries from the car into the kitchen was more strenuous than a week of basic training. Back then the shopping bags were made of paper and half the size of a third grader. The bags had flat bottoms and no handles. The bags had to be held from underneath which meant we had to carry them into the house ONE. AT. A. TIME. Thankfully, unpacking the bags was more rewarding than unloading them from the car. Processed, packaged foods were appearing at a rapid pace, all new and exciting. Each of mom’s trips to the grocery store resulted in some new discovery. There were Ruffles potato chips. It was true; they did have ridges! Chips Ahoy made chocolate chip cookies a treat for the everyday instead of just special occasions. If we wanted to be more sophisticated, we tried the Pepperidge Farm cookies. There were also Pop-Tarts, Bugles, Cool Whip, Spaghetti-Os, Doritos, and that new-fangled potato chip, Pringles. The “treats” were intended “for the week,” but we were lucky if we could scrounge up a single crumb by Sunday night. We eventually got dressed, but it was Saturday clothes, our most comfortable, worn-out, mismatched play clothes. We had chores to do, but the pace was slow and the chores unique. I sniffed a lot of Lemon Pledge, but the antidote was time spent hanging wet clothes out on the line to dry where I could hear the sounds of lawn mowers and enjoy the scent of freshly cut grass. Saturdays wound down with dinner together as a family followed by dishes and more television or board games and Nancy Drew books. If the weather was pleasant, we played outdoors until it was too dark to see or until the mosquitoes drove us back inside. We all slept well on Saturday nights. And then it was Sunday. Sunday was pleasant, but it was no Saturday. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed