all of the selves we Have ever been

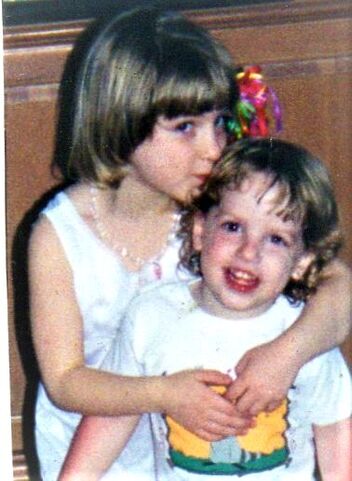

"You don’t know how lucky you are to be loved,” Meg said in a startled way, “I guess I never thought of that. I guess I just took it for granted.” – A Wrinkle in Time We didn’t know it then, but it would be the last time we would all be together in this common joy, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandchildren, great-nieces, and great-nephews. It was a reunion engineered by Cousin Marcia. “Just cuz," she said. We came from far and near toting car seats into the home where once we had been carried as babies ourselves. Familiar voices slipped out of the house and onto the front porch as soon as the door swung open. Inside, the table overflowed with favorite foods that smelled of home, prepared from cherished family recipes passed down for generations. With every seat in the room already taken, our bottoms rested on the upholstered arms of chairs even as our own arms clung to the shoulders of people we had loved for a lifetime. Out on the basketball court, just beyond the kitchen door, Cousin Tom lifted petite second-cousin Elizabeth onto his shoulders so she could dunk a basketball. In this home, we first cousins were simultaneously young and old—children and grown-ups. If the walls could talk, they would remember each of us. Somewhere in this precious place, our childhood shadows were stuffed into drawers awaiting our returns. Here, now, our children sat on the same porch steps, ran down the same long driveway, slammed the same doors, marveled at the same tiny bathroom under the stairs. As my own children were being stirred into this love cocktail, my eyes surveyed the property that had once been a fantasy island: the built in-swimming pool, a pasture where a horse had grazed, a play house, a basketball hoop, a tennis court. The ghost of a sleepy Lassie dog rested on the warm asphalt taking it all in too. Inside the house, books lined the living room shelves and a piano occupied the space in front of the window. This place had been our personal Magic Kingdom where every childhood interest had been encouraged. “…the joy and love were so tangible that Meg felt that if she only knew where to reach she could touch it with her bare hands.” – A Wrinkle in Time Through the archway I saw into the family room where my mother sat illuminated by sunlight and memory. The brilliant and beloved youngest of my grandmother’s many children, mom had a rare moment to be the center of attention. A new generation became her enraptured audience hanging on to her every word. This home belonged to our adored Uncle John and his wife, Aunt Janet. Kind and unshakeable, generous, and a lover of gadgets and emerging technology, if he bought one new item, Uncle John bought nine—one for himself and one for each of his sisters and his brother. Aunt Janet never complained. The latest miracle invention revealed on this Cousin Reunion Day was the hot air popcorn popper. Even as the sun began to set, fluffy, fresh popped kernels rose from the machine’s spout, but even magical popcorn could not make the day last forever. We loaded our cars in preparation for our departures, each of us believing that there would be more popcorn on a future day, that this was the first of many cousin reunions to come. We strapped ourselves and our children inside the vehicles that would rocket us to our homes in distant galaxies and far from this star where all of our lives began. As we pulled away, Cousin Tom stood in the driveway holding a sign: “Does anyone have to tinkle?” We left laughing at this reminder of Aunt Gen’s frequent and famous last words, a necessary question in an extended family where as many as 21 nieces and nephews might be traveling in a single pack. Of course, we had all tinkled! It was a life lesson not eliminated but retained, a lesson written in a family language for words too impolite to shout in public, a tutorial on self-care, being prepared, and showing consideration for others. As the procession of cars inched down the driveway, we looked back at this place that had been our sun. We each had journeyed through space and time on many a quest. Sometimes we returned to celebrate, other times, we returned to console. And then the demands of life grew along with our families. We never reconvened for another cousin reunion. Now, I ask myself, “Where did the years go?” It was all just a tinkle in time.

1 Comment

I’ve lost my edge. And my bounce. After a lifetime of rolling with the punches, my figure can only be described as “round,” and my squishy, inert orb rests on the playing field waiting to be kicked into play. I thought it was my age, but many people of different ages are complaining of a brand of inertia that has become the new long COVID even for those who never contracted the illness. The op-ed columns are screaming with commentary on “quiet quitting,” and yesterday, the mailman shared that he has been delivering mail for 30 years after a stint in the military. His days are getting longer because the post office is short on help. “There used to be a waiting list of people who wanted to work for the post office. It was considered a good job,” he tells me as he fills the mailboxes that line the lobby walls. “No one wants to work anymore. They don’t want to work weekends or long days. They don’t want to deal with the weather…” I feel for him as I rest on the steps watching him work and listening about folks who haven’t quit because they’ve never even taken the field. As if the news media were reading my mind, a headline pops up: Coronavirus Linked to Personality Changes in Young Adults. According to a Florida State University study, the pandemic “may have fundamentally changed the personalities of young people.” The long periods of social isolation seem to have made them moodier, more prone to stress, less cooperative and trusting, and less restrained and responsible. Researchers speculate that these changes may be due to a disruption in the completion of specific and normal developmental tasks and in the maturing process in general. My mind wanders to a Holocaust survivor I have known. He was herded off to a concentration camp when just an elementary school boy. He recalled standing in the morning line-up as wagons passed by the long rows of captives. The bodies of those who had died overnight or in the gas chambers filled the carts and hung from the sides. “These were our loved ones,” this survivor told me. “We were an emotional people, but we couldn’t even cry.” In his eighties, he now wept, grieving the loss of his loved ones along with the temporary loss of his own humanity at that terrifying and tragic time. While our lives in no way resemble the tragedy of the Holocaust, I can appreciate the point of view of the shell shocked, those individuals who have faced intense, life-threatening circumstances that produced feelings of helplessness, fear, inability to reason or to carry on with the normal tasks of daily living. How especially true this must be for children with wild imaginations and limited life experience, perspective, and power. In the last three years, we have been bombarded, not by bombs, but by disasters. First, COVID made its way into our awareness. There were the terrifying unknowns and dire predictions. The lockdowns. The disruptions to travel, daily life, work, school, and supply chains. There were loss and death, exhausted caregivers, and no end in sight. Anger and outrage were directed at the very people trying to assess the germ and protect us from its harm. And while we were trying to find a balance for living, we were inundated with news reports about climate change, wild fires, and shortages of every kind. Our government came under siege as our representatives attempted to complete the ceremonial task of certifying a presidential election. An unprovoked war broke out in the Ukraine, and new horrific war crimes were exposed each day on the news. That was soon followed by threats of a nuclear power plant disaster or the use of nuclear weapons. Fuel supplies were cut or sabotaged. We continue to struggle with skyrocketing inflation as the world teeters on the edge of financial collapse with the British and Chinese currencies in trouble. We have argued long about immigration, and now we are treated to political stunts on the evening news even as the entire world is struggling with mass displacement due to famine, disease, hunger, human rights disasters, war, violence, and climate change. New germs threaten to get us: monkey pox is on the rise everywhere; Ebola cases are increasing in Africa; and polio has been found in the wastewater in New York. Devastating mass shootings and frightening political upheaval are daily news fodder. We learn that we cannot trust people in leadership to reach solutions or protect us even as violent crime increases. And this week, we were served a new poison--a once-in-a-lifetime weather event that has devastated Florida, the Carolinas, Georgia, and parts of Virginia. And continuously humming in the background of all of this is the media shame machine. We have so many new labels to discredit people that we can no longer speak to one another in the civil manner needed to solve problems. No wonder young people are quietly quitting. We are all weary and frightened. Like overstimulated two-year-olds, we just want to take a nap and wake up when the world is all better. My mind wanders again, this time to the people aboard United Airlines Flight 93 on 9/11. When it became apparent that terrorists had hijacked their airplane and intended to do grave harm to the country, these passengers decided to take action knowing they would likely lose their lives in doing so. “Let’s roll,” Todd Beamer is credited with saying. The plane went down but spared the much larger disaster in the making. This morning electrical workers and Red Cross volunteers here in Columbus, Ohio and in many states both red and blue, started their engines. Their wheels began turning. Small armies of the tired but determined left home for disaster zones in Florida, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia. Hang in there, kids. We may be weary, but when it matters, this is how we roll. The restaurant filled up and bubbled with life much like the champagne glasses on the next table. It was the first week in which the world began waking from the long COVID winter. My friend arrived, and we greeted for the first time since it all began. We were each in a contemplative mood, a condition of both our ages and the universal outcome of a pandemic in which there was little else to do but think and worry. Near the end of the evening, as we pondered our futures in retirement and our need for a new sense of purpose, I shared my mounting regret that I had not had the wisdom to ask my aging relatives what it was like to grow older, to ask what their own lives had been like when they were young, to study the path between youth and older age. They had always seemed old to me. Youth was never a condition I imagined in them. Now it was too late. My friend nodded in agreement and shared her own sorrow about the time she spent caring for her beloved and now deceased mother: “I wish I had spent less time managing her, and more time just being with her.” That arrow plucked from her heart pierced mine too. We sat quietly, each bleeding a little on the inside. Both of us baby-boomers, we grew up in a mechanical age of industry and assembly lines. Efficiency experts had been elevated to the stature of gods. We reached young adulthood with business management principles overflowing the factory floor onto our personal lives. Sewn into us was a long, sturdy thread of advice on how to efficiently manage our time, money, children, aging parents, health, weight, and all of our affairs. Self-help gurus were everywhere to remind us that it was up to us; we were on our own. The message came through loud and clear: successful people are competent; competent people are good managers. Both bright gals, we studied the literature. This societal message became the inheritance of our children, too. From the time they entered pre-school, our kids were walloped with advice about how to “build a resume for college”--that ferocious mix of the right schools, academic rigor, homework, arts, sport, and community service. Aspiring to become competent parents, we tried to keep up. Not to keep up was to become a failure and the subject of gossip and criticism. Any life troubles were assumed to reflect our botched management: a failure to manage the retirement portfolio, a failure to manage the child’s education, a failure to manage the care of aging parents, a failure to manage health care screenings, a failure to manage the social media presence, the in-boxes, the on-line images, the professional brand… We knew what the neighbors were saying: “if only they had been better managers.” In mid-life, we entered the digital age. A host of new tools fooled us about time savings and the actual distance between people. Our tools became another distraction in the service of helping us to manage. But much got lost while we were busy managing no matter how fancy the tools or how many bytes in the memory. Time ran out. Parents died. The children grew up. Friends moved away. While the forms were getting signed, the tuition paid, the countless appointments kept, we forgot to drink up the moments and the company. Blinded by the demands of life and the counsel of experts, we believed the successful completion of tasks was the relationship. We forgot to be present. Oh, what I would give to go back in time for one more day, to snuggle up with my children in our big comfy chair with nothing else on my mind save for their sweetness and warmth! Or a quiet Sunday gathered around my grandparents’ kitchen table to talk about their youth and their dreams. Were their dreams realized? Did it matter? The grandparents are gone now, the parents, aunts, and uncles, too. The children are grown and busy. They are managing their own lives. And this generation that grew up building their resumes for college is not giving us grandchildren. There is already too much for our kids to manage. As I move toward the age when I will become the managed and not the manager, I am aware that the issue is not unique to my friend and me, a couple of women with a few regrets. The pandemic awakened a realization in all of us that managing our lives is not enough. We isolated, masked, sanitized, and sacrificed and still could not hold a tiny germ at bay. We learned that life can be fleeting, surprising, and sometimes tragic no matter hard we work to manage it. Perhaps the post-COVID labor contractions reflect the birthing of a new way of living in which we will care for ourselves and each other at all stages of the life cycle, not with our clocks and our calendars, but with our time and our presence. When my own life ends and the children come to clean out the closets, I hope they will find important dates still circled on my calendar, a reminder of happiness to come, a few cherished mementoes stashed in the attic that link them to their past and to me, some presents tucked away for their future holidays, and a cup of joy upon the stove to sip and to share as they sort through all of the pieces of a long life. When the cupboards are empty and their trunks are full, I hope they find that they had plenty of love and no regrets.  The long pandemic year left me feeling youth-deprived. With my own children grown, no grandchildren, and social distancing, my world was bereft of children. About the time I began to acknowledge this painful loss of youth, my friend Laura wrote about her encounters with the neighbor’s grandchildren. These kids gathered on Laura’s porch for a few consecutive days. They visited, borrowed toys, and made up stories. It was lovely to imagine the good fortune to spend a few summer hours in the company of creative, curious, energetic children. I was both awed and envious. With that on my mind, I stopped at a fast food restaurant. Still in pandemic mode, I intended to place my order at the drive-through window, but the line was so long that I decided to live dangerously and go inside. As I stepped up to the patio that surrounded the front door, I discovered the area littered with boys on a lunch break from the neighboring high school. These youth spread out like water in that fluid way of lanky teenage boys who travel in packs. The entire bunch gathered around a single table. Some of the boys sat on the small benches, others stood, several shared the edge of the same bench—three where one was meant to sit. Their backpacks and belongings took over the remaining space. When the boys stood, their bodies stretched up into the heights of adulthood even as they remained cloaked in the soft, tender flesh of childhood. Talk and laughter emanated from their smooth faces. They elbowed each other and snagged French fries from other trays. They conferenced and negotiated a deal in which each of them would have enough money to return inside to purchase a small frosty. The first boy in line passed his change to the guy behind him and so on until the last man standing was served his frozen dessert. They were polite in passing and held the door for me. They seemed free and happy. Together, they were able to stand strong against that inner, invisible critic that makes teens self-conscious in the company of adults. They deftly walked the line between awkward and cool. As though they could hear the school bell ringing, the group abruptly stood and left the patio. At the same moment, they all stepped off the curb and into the middle of the street, ignoring parental teachings to cross at the corner and wait for the light to turn green. This long gaggle of parentless goslings stretched the entire width of the road. Just as suddenly as the group departed, two of the boys raced back to remove the trays and the trash. A boy with the name Murphy printed across the shoulders of his football jersey remained until the patio was clean, and then he raced to catch up with his peers who were already out of sight. The middle-aged woman who manages the restaurant laughed and shook her head as she gathered up the backpacks and belongings left behind. “They’ll be back,” she said. “They always leave something behind.” With this brush of youth, my own smudged, grey outline of a life regained its color, texture, movement, and meaning. Nature was back in balance: young and old, past and future, uniting in the current moment to become the living present I needed. Accepting adults cast a gentle net of supervision and were there to pick up the pieces as these young people stepped off the curb and into the traffic of life. Murphy, who returned to complete the clean-up, was already becoming one of us. There have been moments during this pandemic when it felt like it might be the end of the world. In such a mindset, it can be difficult to remember that life is just beginning for others eager to grow up. Now, at the very moment we thought that we were putting the pandemic behind us, a new variant looms. The virus will do what viruses are born to do: mutate, strengthen, find new hosts, suck the life from the living, and gather speed while doing so. The virus will now come for our youngest citizens—our children for whom there is no vaccine. Our children do not have the luxury of saying, “Give me liberty or give me death,” ill-conceived as that current use of the word liberty may be. Our children are now the most vulnerable. They trust us. They have no other choice. Trust is the foundation of all meaningful relationships, the core of our humanity. Trustworthiness characterizes the mature adult. Toddlers are egocentric by nature. They first have to realize they have agency in order to exercise it in the future. When they throw themselves down in the cereal aisle and demand some sugary food, they do not have adult understanding, insight, and judgment. Those wee ones lack the powerful adult capacity to anticipate the future and to harness dangerous desires. Their needs and wants remain immediate and all-consuming. Under healthy circumstances, they will grow out of it. The gift and the burden, the obligation of adulthood, is to look after the young, to ensure that there is a future for them just as previous generations did for us. Our ancestors took the smallpox vaccine and the polio vaccine. They accepted their war rations and lived within those meager means. They planted and harvested their victory gardens, and they resumed life and making a living even as they were shell shocked from war. As adults, we are not the center of the universe, but it is our job to keep the earth on its axis and to keep it turning for the sake of our children. I understand that there may be many reasons an adult would not want to take the new, emergency-use vaccine. But that does not relieve adults of the obligation to wear a mask, social distance, and stay away from mass gatherings, to protect our children. I do not want to live in a world deprived of youth. And so, for our children, I offer this prayer: Please, grow up. And to the minority of childish, angry, and egocentric adults, I make this plea: Please, grow up. Let’s respect the natural order and be the ones to leave something behind.  A friend and I chuckle about a son’s comment that “adulting is hard.” Our young 20-something children are surprised by the daily demands of adult life: When must you go to the doctor, and when can you wait it out? How do you handle health insurance claims, purchase a car, come up with rent and a security deposit, file an income tax return? My friend and I know that the list is endless. We begin “adulting,”or trying on adulthood even as preschoolers during dress-up play. We put on dad’s shoes trying to understand how it feels to be him. We carry mom’s briefcase around emulating her dress and behavior. But when do we really become grown-ups? Where is the line in the sand? Is it when we turn 18? 21? After we have voted in our first election? Upon graduation from high school? College? After we get “a real job?” I think about my years in graduate school. Legally, I was an “adult.” I made my own medical appointments and took care of my own health insurance. I purchased a car and paid my own rent, filed my own income taxes. Was I really an adult? During those years in graduate school, I had a very close friend named Will. Will’s wife became pregnant during our second year in the program. We were all broke and exhausted from full time coursework, internships, and jobs that did not pay well. We didn’t have much, but we had each other. Life was fueled by cheap coffee and wonderful camaraderie. We focused on survival and hanging out with our friends. The day Will’s daughter was born, Will called me with the news. Will described the childbirth experience from a new father’s point of view: “Something remarkable happened,” he said. “The instant she was born, everything mattered. Just like that, I cared about HIV, toxic waste, and the Cold War. Everything mattered because of her.” Abracadabra! It had happened. The news was much bigger than just another birthday. Suddenly we were no longer carefree graduate students with our little problems. What happened in the world mattered to us now because someone small and vulnerable mattered even more. As children, we were shielded from the terrifying realities of the world. We did not have the knowledge, wisdom or insight to worry about toxic waste, the Cold War or HIV. We felt secure in our nests surrounded by adults who seemed so powerful to us. We trusted that the world was in good hands. Sometimes having a child can shake us out of complacency or bring us into the realities of adulthood. It does not work for everyone. And it is not necessary to have a child to become aware that we are now responsible for what happens in the world. Perhaps, there is no particular age at which we make the giant leap over that line in the sand. We become grown-ups at the moment when the issues of the day begin to matter, when we can no longer look away or look toward someone else for all the answers. We become grown-ups when we feel the weight of the future and acknowledge that it is now in our hands. And then we make a deliberate commitment to care. Our kids are correct. Adulting is hard! |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed