all of the selves we Have ever been

“Mom, I hear her!” At the insistence of my seven-year-old son, we follow the laughter into the next aisle. But it is not her. It could not have been. She was murdered a few weeks before—a teenage girl with a life full of promise and a chest full of gunshot. A paranoid and obsessed boyfriend took her down in her own apartment. Her parents heard the news on the car radio while driving to work. And yet, here she is--a niece, a cousin--in Wal-Mart, aisle four. Attention shoppers! For a moment, she returns to us in notes of laughter, a song that should have been hers but wasn’t. Feelings of unreality, yearning, and hope unite with memory. Does she message us from heaven? *** I busy myself at my desk, peering intently into a computer screen. Suddenly, I smell her. “Sita? Is that you?” I follow the scent into the kitchen. But it is not her. It could not have been. She died 57 years ago from complications of diabetes. Three thousand miles away, my family got the call. And yet, here she is—a beloved grandmother—in my tiny galley kitchen. For a moment, she returns to me in the scent of lentils simmering on the stove. Lentils--a food we ate so often in her home that they became the eternal fragrance of her flesh. Is this comfort in a pandemic? *** It is midnight. We are watching Johnny Carson when the bells clang at the village church nearby. Across the living room, I see my aunt sit up straight in the recliner chair. Her body stiffens. “Can it be?” I follow her to the front door. We look outside. Never have I heard these church bells ring. My aunt tells me that the ringing ceased when World War II ended. With no more casualties of war to report, the bells went silent. And yet, here we are—in a town where families still grieve over soldiers lost, remains unreturned. On this dark, still night, is a son reaching back from the ashes of war to say I am found? *** Are they here? Or are these experiences sensory tricks played on suggestible minds? Are the heightened emotions and tensed muscles products of overactive imaginations? If so, explain that to the preschool child in foster care who collapses in grief at the smell of baking bread. He carries a burden of grief for a mother he can no longer name, a face he cannot recognize. And yet, her love reaches out to him through an oven door. *** No, these occurrences are not imaginings. They are more than the prosthetic memories produced by cell phones and machines, more than Hollywood special effects. They are not images distinct from our own beings. These special occasions are rememberings. Through a cosmic miracle, the remembered are present, a presence that is real though invisible in the same way that a giant sequoia is fully present inside a tiny seed. In these moments of remembering we are equally present and engaged with those we have loved. In his book, Remembering, Edward Casey wrote that remembering happens both WITH and IN the lived body. “…we come back to the things that matter.” Casey describes his own nostalgia for these experiences: “it is insofar as they are unrepeatable that these remembered times beckon so movingly and powerfully to me in the present.” In my own moments of remembering, I understand why the ancients believed in spirits and an afterlife and why those beliefs have persisted for thousands of years. The words of the Old Testament tell us that the giants of those Bible stories were “gathered to their people” when they died. I am grateful for rememberings-- when my people gather here for me.

0 Comments

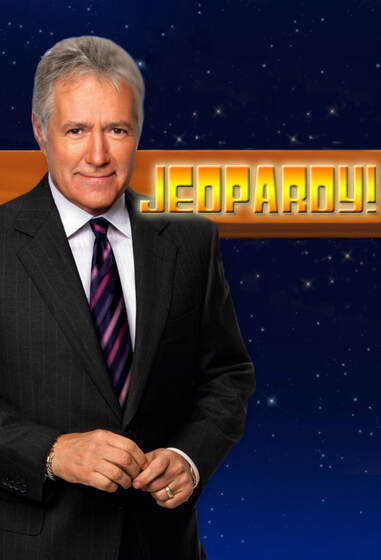

The truth is out. Upon hearing it, I nearly fell over right there on the spot. The revelation came from a colleague of mine who owns a poultry farm. She and her family raise chickens for a giant national food corporation. Concerned about slow-downs at meat processing plants earlier in the pandemic, my co-worker happened to mention that the birds would have to be killed if they could not get to the processing plant in timely fashion. Apparently, if the hens’ breasts grow too large the chickens topple over. They fall and they can’t get up. THE END. It was an “aha” moment for me—a premonition. My life passed before me, and I realized--this is how I am going to die. Women of a certain age and build will know what I mean. Now history makes sense. This is how women became doormats in the first place. I took a whiff of ammonia to keep from fainting and recognized the smell of a multi-generational conspiracy to keep women down. There are oceans of little blue pills for men who can’t get up, but nothing for this age-old problem affecting women. Is there no little pink pill for pectoral dysfunction? While I can picture the final tipping point, what is harder to imagine is the coroner’s report. What exactly are the words used to describe the cause of death? Is it simply natural causes? Or is there something more medical, more official? Terminal sagacity? And what does one write in the obituary? Perhaps it happens suddenly, but at a certain point, it can’t be unexpected. Surely, a woman sees it coming. Should tributes be described as a battle? A journey? Would it be too crass to say, “She could no longer stand up for herself?” And what of the arrangements? Should it be open or closed coffin? After the cause of death is revealed, you know visitors won’t be able to manage their eyes. How awkward for the family. And what does one say in condolence? Something uplifting? Now that I have had this glimpse of the future, I can spare you that uncomfortable expression of sympathy. When my time comes, just say: “She was larger than life."  “The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul.” (1 Samuel 18:1) I treasure this ancient and beautiful description of friendship and the image of souls knit together into one fabric, a cloth fashioned from threads that are soft and strong and deep. A similar description in the book of Mark describes marriage: “and the two shall become one flesh” (10:8). Like Davidandjonathan, we all know relationships that share one name in our mental directory: Rickyanddennis, Maryandbill, Betsyandjoe, Bobbyanddenise, Momanddad, Nanaandpop-pop, brotherandsister, husbandandwife, parentandchild. When one dies, our minds struggle to compute. For the surviving half, the ache of loss can become like phantom limb pain. It is not psychological, as in “all in your head.” It is not “unresolved grief,” or “complicated bereavement.” As the brain continues to remember the missing limb and continues to try to communicate with it, so the soul still speaks, activating emotions, trying to connect with the missing member. Dr. Gordon Livingston who experienced the deaths of two sons, one from leukemia and one from suicide, writes in his book Too Soon Old, Too Late Smart: “Like all who mourn I learned an abiding hatred for the word “closure,” with its comforting implications that grief is a time-limited process from which we all recover.” During this year of 2020, we have experienced so much tragedy. The pandemic alone has generated a landslide of loss. Add to that disaster the unprecedented wildfires, a record hurricane season, increases in violent crime and murder, and deaths from drug overdoses and suicides. There are so many who have been ripped apart from their other halves, carrying on with aching, missing limbs. And there are the thousands of health care workers who were present as the threads were cut who will forever carry the memories of those moments and the grief absorbed. A vaccine is coming. This viral-crisis will end, but words like “let the healing begin” or “getting closure” will be inadequate. There is not a starting line and a pistol shot to mark the beginning, and there is no finish line. The effects of this difficult year will be felt not just individually, but in our national soul forever. In Greek mythology, Pandora opened a jar containing sickness, death, and evil. Before she could close the container, all of that darkness escaped into the world. Pandora hurriedly closed the container, and all that remained in the jar was hope. Dr. Livingston offers some advice to other survivors of loss. He writes not about closure or healing, but about hope: “This is what passes for hope: those we have lost evoked in us feelings of love that we didn’t know we were capable of. These permanent changes are their legacies, their gifts to us. It is our task to transfer that love to those who still need us. In this way we remain faithful to their memories.” Today, there are millions in mourning. We must call upon our better halves and transfer some of that love to those who need us.  I knew them both. A few short miles separated their houses. A greater distance separated their lives. He had everything, it seemed. She had nothing. Their ages differed by more than fifty years. He had passed the age of ninety. She was barely thirty-five. A wide gulf separated their achievements. He was a decorated soldier, a retired corporate executive, and a practicing lay minister. She worked in a hotel, making beds and scrubbing toilets. He created a family that spanned many generations, and he had lived to see the children of his great-grandchildren. She would not live to see her only child go off to kindergarten. His stately home was built of brick and sat beaming on a cul-de-sac in an old, established neighborhood. A yard sign advertised his house on the Holiday Tour of Homes. In the garage, a boat kept company with a luxury automobile. His home was paid for. He had money in the bank and two hefty pensions. He lived each day surrounded by tasteful furnishings and expensive collectibles. She lived in a modest tract home in a low-rent neighborhood where broken-down vehicles lined the streets. A security camera on the house next door blinked the steady reminder of a break-in. Her small Ford was parked in the driveway, but it really belonged to the bank, not to her. She had no savings. Bill collectors called. She hoped to receive a disability check. Holes from a man’s fist, holes from her head accented the walls. He had the pleasure of a marriage that lasted more than fifty years. He said his wife was his closest friend. She awaited the arrival of a divorce decree. She said she still loved the man who put the holes in the walls. Despite his training and ministry to others, he believed that God was a son-of-a-bitch with a bad sense of humor. She had no religious instruction but hoped that God was kind and watching over her. He had many well-educated and capable adult children who tried to care for him, but he chased them away with his irascible disposition. With grace and patience, she allowed a mentally ill mother and a drug-addicted sister to care for her, to rise above their means and their own problems, to be better and braver than they might otherwise be. He greeted every day with contempt and hostility. He behaved so badly that a sigh of relief was offered to heaven when he passed suddenly and alone. She was surprised and grateful to open her eyes each day. She was showered with attention, tender care, and kisses. Heaven’s gate opened wide to a woman loved. Appearances can be deceiving. He that dies with the most toys is not always the winner. In the end, when both had died just days apart, she was the one who had everything.  In a year in which we have felt that everything we hold dear is in jeopardy, a final blow—we lost the man with all of the answers. Jeopardy! has been on the air since 1964 beginning as a daytime television show, but those first twenty years were just a warm-up for the real headliner, Alex Trebek, who stepped onto the set in 1984. Folks like Khloe Kardashian, Mark Zuckerberg, LeBron James, Mandy Moore, and Lindsey Vonn who were born in 1984 spent their entire lives with Alex Trebek. He was Jeopardy! Several generations have grown up or grown old with him in their living rooms each evening. Jeopardy! is the game that brought us all together. It was a TV trivial pursuit, but it didn’t feel trivial. We played along with those Jeopardy! contestants feeling scholarly and wise. Young and old, we shouted out answers. I knew my children were grown up when they became the ones with the correct responses. Unlike so many other contests in life, there were no losers on Jeopardy! It was an honor to play the game. To be chosen as a contestant elevated a person to the category of intellectual. For those of us playing from home, a single correct response gave us hope, elevating our own self-esteem. For those thirty minutes each evening, we experienced the power of engaged minds. There was nothing else in the universe. No worrying. No arguing. No ruminating. We played the game. This week, I have come to an aching acceptance of an empty chair in my living room. The game will go on, but there will always be someone missing. There will be dinner each evening, but no dessert. There was the game, and then there was Alex Trebek. He was handsome and recognizable at age 50 and still at age 80. Alex was a star in his own right, but not tabloid fodder. He was low key and projected a world that was better than we thought it could be. The most shocking thing he ever did was shave his mustache. He was not one to be outrageous for the purpose of seeking attention, but he was known for his sharp wit—even his humor was intelligent. He was a good sport and made an occasional appearance on Saturday Night Live and once traded places with Wheel of Fortune Host Pat Sajak as an April Fools Day joke. His gentle life was a lesson though he did not preach. We felt the lesson just as much as we could see it. He emanated decency and old-fashioned manners. Alex Trebek was smart, articulate, steady, graceful, and gracious. His presence was comforting and reassuring. A stickler for the rules, he was not a judge. If the clue was “Salt of the earth,” the correct response would be: “Who is Alex Trebek.” In spite of the popular advice to “find your passion,” we saw a man who had found his niche. He seemed to understand that life’s answers often come in the form of a question. Equipped with knowledge, a person can ask the right questions. As Jeopardy’s Executive Producer Mike Richards recently stated, Alex Trebek “made being smart cool.” A Holocaust survivor once told me that he looked forward to heaven because “that’s where all the answers will be.” I smile now as I recall those words that this week became a prophecy. Heaven is where all the answers will be. Alex Trebek will be our host. “I’ll take ‘Enlightenment’ for a $1,000, Alex.”  “A thundering velvet hand...” “A gentle means of sculpting souls” Those are the words that Dan Fogelberg used to describe his father, a school band director. After the song, Leader of the Band, became a hit, Fogelberg said in an interview that if he had written only one song, Leader of the Band would be it. His father was surely someone remarkable and loved. Another singer-songwriter, Bill Withers, wrote and sang about the hands of his maternal grandmother, Lula Galloway, with whom Withers attended church on Sunday mornings. Lula used those gnarled hands to clap and sing in church and to protect and nurture her grandson. Withers wrote “Grandma's hands picked me up each time I fell…If I get to heaven I’ll look for Grandma’s hands.” We are each born with our lives in someone else’s hands. Throughout life, we rely on safe hands. Kind hands. Gentle hands. We remember the helping hands. In our family, we are all thumbs. When my son Sam was a toddler, we had a bedtime routine. I would lie down beside him for a few minutes as he settled into sleep. Sam would wrap his chubby little hand around my thumb, and I would sing as he fell asleep. At bedtime one busy evening, I was unable to stop what I was doing in order to get Sam to bed. My daughter Emily, Sam’s sweet and earnest big sister by three years, said, “I’ll lay down with you, Sam. You can hold my thumb.” Sam shook his head. “No, Em-a-wee. I need a BIG fum.” I understand. I had a big “fum” when I was a child. That big thumb was attached to the right hand of my Uncle John. He was not a band leader, but Uncle John did have one of those thundering velvet hands. He was a gentle soul and a giant in my life story. He deserves his own song. Uncle John made it his mission to shape the souls of a huge tribe of nieces and nephews in addition to those of his own five children. I don’t know how it began or why, but whenever Uncle John came into our presence, he extended his hand, “Touch thumbs,” he would say, and our little fums shot up, and we made contact. It was a safe and convenient display of affection, especially when Uncle John was in the driver’s seat transporting a station wagon full of squirming children to the swimming pool or the custard stand. Before he started the engine, Uncle John would turn to face us, extend his right hand, thumb up, and each of us would jockey to reach him and touch our thumb to his. The journey did not begin until each of us had made contact. Towel? Check. Sunscreen? Check. Seen and loved? Check. Check. Sometimes on a Sunday morning, Uncle John would slide into the church pew next to me. He might reach out his thumb or wrap his hand around mine. Once in a while his hand would slip a silver or gold bracelet into my pocket. Often when we parted, Uncle John would slip a twenty dollar bill into the palm of each of the gathered nieces and nephews. He continued the tradition long after we all became working adults. Nothing escaped Uncle John’s view, but he never used those hands to “stir the pot,” an amazing accomplishment in a large and highly emotional extended family with enough teenagers for plenty of trouble. Touching thumbs was an act that never got old or lost its power. When my daughter Emily was born, a C-section turned to near-disaster with a life-threatening hemorrhage. After a touch-and-go stay in the intensive care unit, I was sent to a regular room on the obstetrics unit. Just settled in my bed still surrounded by IV poles, so full of fluid I could not blink my eyes or bend my knees, I turned my head to the left, and there was my Uncle John and his wife Aunt Janet. Upon seeing them, I began to weep. All of the terror and exhaustion of the past few days came bursting out of me. They came to the bedside. Uncle John’s jaw was tense, his lips tight and twitching at the right corner as he blinked away his own tears. He reached for my left hand and touched my thumb with his. We were frozen in a moment of terrifying what-could-have-been and then relief. The healing power of big fums! Many years later, I would stand in an intensive care unit alongside the bed of my cousin Marcia, Uncle John’s baby girl. A heart catheterization turned disaster. Marcia did not open her eyes. As the ICU nurse sorted the tubes and monitored the equipment, I wanted the nurse to know that this woman, our Marcia, was someone special. I told the nurse about Marcia’s life and accomplishments, and then I touched Marcia’s left thumb with mine. By morning, Marcia was gone. When it is my turn, and I get to heaven, I’ll look for those hands. I will know them by their thumbs.  Joe Morgan died this week. The headline popped up on my web browser home page. There are some who looked at that headline and said, “Who?” Others may have seen the news and thought, “Who cares?” Me? I was pierced by sadness. I immediately emailed my best friend from high school with the news. I knew she would understand. They were young, and so were we. They were major league baseball players. We were high school students. They took the field. We took our seats in the stands--as often as we could. We were all in the middle of something. My friend and I lived in Pittsburgh. We were Pirates fans. The 1970s was a great decade for baseball in the tri-state area. The Pirates and the Reds were both powerful teams and fierce competitors. It was the Lumber Company versus the Big Red Machine. We watched the greats like Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and Bob Robertson go toe-to-toe and bat-to-bat with Joe Morgan, Pete Rose, and Johnny Bench. When the Reds came to town, it was guaranteed excitement. Sometimes the heat of competition spilled over into a brawl on the field. Joe Morgan was particularly memorable. Stepping up to the plate, bat in hand, his back arm bent and flapping like a wing, Joe was part eagle about to take flight. His stance was twitchy, like the ball was already out of the park, and Joe was late for his date with home plate. My friend and I saw a lot of games. We saw many young men hurl their first major league pitches and step up to the plate for their first swing at bat. Not all of them rose to greatness in the history of the game. Not all of them stand out in our memories. Some, like Joe Morgan, became legends. We are moved by their passing. My sadness today leaves me to ponder the question—Why? Like the millions of stars that fill the night sky, it is only a few that reach us with their brilliance. They beckon us to look up. Fans are stargazers. They know where to look in the night sky. They study the stars, count them, and give them their names. We were witnesses to their lives. We clapped and cheered, game after game, as all of those games added up to something remarkable. We watched our heroes transform from youthful rookies into seasoned veterans even as our own youth slipped away. Their lives and careers became mile markers on our personal journeys and pages in our collective history. They belong to us and to our national treasure chest. Like so many of the balls he hit, Joe Morgan has left the park. Like the stars, his brilliance lives on. I will think of him each time a rookie steps up to the plate and an umpire cries, “Play ball.” |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed