all of the selves we Have ever been

I went into labor on Labor Day. The holiday that traditionally defines the end of summer was about to redefine my life. By midnight contractions were coming close together. The doctor could not be reached, but the answering service advised me: “Get to the hospital.” Almost two weeks past my due date, my husband and I were ready. The hour-long drive to the hospital took on the extra seriousness that travel takes in the lonely, dark hours of the night. I timed my contractions by the glowing blue digits of the dashboard clock, reassuring myself that this was no false alarm. My husband and I did not speak. He concentrated on driving and kept his thoughts to himself. My own mind was stirring with both concern and excitement. It had been a long nine months. This pregnancy followed a painful miscarriage. While delighted with another pregnancy, life had not been easy. I suffered from serious anemia; the low-iron fatigue was complicated by repeated travel from Ohio to California where my father was dying of cancer. In between trips, the old pipes in our home blew out and all of the plumbing had to be replaced. Both my life and my home had been torn apart, but, at last, a wonderful new chapter was about to begin. We arrived at the hospital where I was assigned to a labor room and placed on monitors. The hours ticked by with no increase in the intensity or frequency of contractions. Drugs were added to an IV in an effort to move things along. One-by-one signs appeared that a baby was on the way and so did the signs that it was a baby in distress. The decision was made to proceed with a cesarean delivery. A nurse anesthetist began the epidural. Almost immediately I felt a strange, intolerable heaviness from my lower back to my toes. I focused all of my energy on holding my body together. Tingling and discomfort moved up my spine, through my neck, and to the back of my head. In the delivery room I struggled to maintain consciousness. My mind began to register that something was terribly wrong. “I should care about this but I can’t,” I thought. It was like someone had thrown a switch in my head that separated my emotions from the reality of the emergency taking place. I was more apathetic observer than participant. At 3:12 PM my daughter, Emily, was born. She was wrapped in a blanket and handed to her father who turned Emily’s tiny, red face toward me as the staff whisked both father and daughter from the room. The doctors finished their work. My eyes next opened somewhere in a hospital corridor, and then I was out again. The next moment of awareness came as a young nurse approached my bed in the recovery room. I could see her face coming closer. “Something is wrong with me,” I said. “I’m all wet.” The nurse lifted my covers. I heard her cry out, “Oh, my God!” and I faded again. When next I came to consciousness my obstetrician was standing at my bedside yelling, “Where’s the father?!” Fourteen pairs of legs surrounded my bed, each connected to a pair of hands working on some separate part of my body. Blood was pouring out of me and onto the cart, dripping down to form a puddle on the floor. “Fifty-over- thirty,” a woman’s voice called out my blood pressure. I was shaking with cold. In his desperate haste to get blood into me, the young technician preparing the transfusion had by-passed the blood warmer. “This is how dead feels,” I said to myself. “I am going to die,” became my last terrified thought, and then a sweeping sensation lifted me backwards off the bed. I transcended the room completely oblivious to the lifesaving efforts and drama being played out on the bed below. My entire life passed before me--not like the play of a videotape on fast forward as I had always imagined, but an overwhelming sense of my entire life presented in the capsule of a nanosecond. I felt comforted, but the comfort did not last. A vision followed: my baby daughter, no longer a newborn, looking straight over her daddy’s shoulder and into my eyes as her father carried her away from me. The depth of sorrow her eyes conveyed was unbearable. I prayed: “Please, God. I have to make it back. She cannot grow up in that kind of sorrow.” In answer, a commanding presence, not really a voice or an image, pressed me: “Choose!” The rest of that very long day is recorded in my memory as a series of snapshots taken in brief moments of consciousness: procedure rooms, doctors behind glass walls, strange other voices, my own voice screaming in pain. The next day was not much better as I came to consciousness in the intensive care unit not sure if I would live. My husband went between the hospital nursery and the ICU bringing instant Polaroid snapshots of our daughter. Each time a new photo was taped to my bedrail, my husband gave me an update on the babies leaving the nursery for the neonatal intensive care unit at the nearby children’s hospital. Despite my confused and agitated state, I thanked God that it was me and not my child struggling for life. After a couple of days in intensive care, I was moved to a regular post-partum room. Still tied to multiple IVs, I was a virtual prisoner of tubes. In addition to being extremely weak, I could barely open my eyes or flex my fingers due to swelling from the copious amounts of life-saving fluid I had received. As soon as I was settled into my bed, a nurse appeared with my daughter in her arms. When she placed Emily into my lap, I immediately noticed two large red marks—one on the center of Emily’s forehead and the other at the nape of her neck. “Angel kisses,” the nurse stated as she reassured me that these marks were innocent and would likely fade in time. Our room soon filled with the balloons, flowers, and cards that had been waiting for my step-down from the ICU. So many prayers and good wishes! I received multiple copies of one particular greeting card. Each copy came from someone different and unknown to the others. The message: “For His angels will watch over you and guard you in all your ways” (Psalm 91:11). That psalm became my mantra in the following days and months of recovery, an antidote to fear and discouragement. I have faced many hard times since Labor Day 1990, but none so terrifying. In each instance it seems a guardian angel has been nearby continuing to watch over me. And the baby whose sorrow saved me is now an exceptional young woman of great competence and deep goodness. Others tell me so. Of course, I know this. She is the gift of an angel with the kisses to prove it.

0 Comments

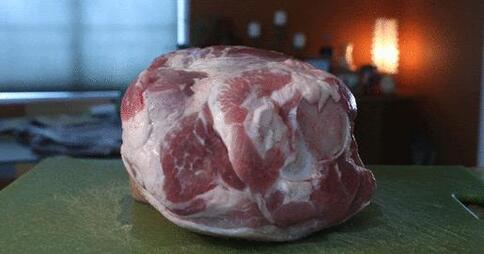

Start the presses and spread the news! There is still time to shop. It is National Oreo Cookie Day. If ever a cookie deserved its own holiday, it is the Oreo. I don’t even mind if the government halts mail delivery. Oreo is the signature product of the National Biscuit Company, the food manufacturing giant better known as Nabisco. The cream-filled cookie also made Hoboken, New Jersey famous for something other than its view of Manhattan. A grocer in Hoboken was the first to sell the treats in cans for twenty-five cents a pound. No one knows where the name Oreo came from; perhaps it is O for the O-shaped cookie, or O for the “Ohs!” uttered by the tasters in Nabisco’s test kitchens. I once thought the Hydrox cookie was a sad wannabee, the second born, a disappointing substitute, but it turns out Hydrox was the first chocolate sandwich cookie of that type on the market. Hydrox made its debut in 1908, four years before Oreo’s introduction in 1912. The Oreo has been the best-selling cookie ever since. Sorry, Hydrox, nice try, and a good idea…but the name Hydrox sounds more like an antiseptic, and the taste, compared to an Oreo, well…a lot like the taste following oral surgery. The Oreo has stayed strong through two world wars, a great depression, and a bazillion weight loss trends. The beloved cookie now comes in double-stuffed, thins, minis, Neapolitan, and Mega Stuff. As of 2019, 450 billion Oreos were sold worldwide. Add the consumption during the COVID pandemic year, and I am sure sales have easily climbed to 1.9 trillion. The National Biscuit Company was granted a trademark for the Oreo on March 14, 1912. National Oreo Cookie Day is celebrated on March 6th because that is the day Nabisco made its application for the trademark. That makes two miracles for the Oreo—the greatest cookie of all time and the fastest turnaround by a government office in history. The product’s tag line is “Milk’s favorite cookie.” Sure, there are a lot of dunkers out there, but there are many ways to eat an Oreo. The best known strategy is for “a kid to eat the middle of an Oreo first and save the chocolate cookie outside for last.” The process is important. Lifting or prying the cookie apart is much less effective than the gentle twist that leaves the creamy layer intact to be scraped off by the eater’s two front teeth. Oreo fanatics have expanded the brand. Oreos are now a staple like flour or sugar. Oreos appear in recipes for pie crusts, pies, cakes, ice cream, milkshakes, candy bars, and are even coated and deep fried at county fairs. Oreos are a snack, a dessert, a special treat, and paired with milk, they are practically a health food. The standard package notes that a serving size is three cookies with twelve servings in a pack. Really? Who can eat just three? I suspect that an entire row is more typical. Three Oreos? That just wets the appetite because Oreos are as addictive as cocaine. They are the preferred party drug of the tea party crowd. Decades ago, I experienced an Oreo overdose. My mother had gone to the hospital to deliver a baby—my brother or sister? I can’t remember because the real event was the Oreo tea party authorized by our father to keep my older sister and me out of his hair. Mary and I each consumed far more than the suggested serving of three Oreos. For dessert, we topped off our tea party meal with the Oreo’s favorite cousin, a bag of M&Ms. When it was time to retire for the night, my sister and I climbed into our bunk beds that were covered with matching white chenille Sleeping Beauty bedspreads. Initially, our stomachs gurgled just a bit, but before we could fall asleep, our guts erupted like Mount Vesuvius. Eventually, we slept well. The nightmare came for our mother who returned home with a new baby and plenty of laundry to do. The entire episode was easily forgotten by me and my sister. It may have contributed to our parents' later divorce, but Mary and I never fell out of love with Oreo cookies or tea parties. Oreos have been around a long time. Even their current design has remained unchanged since 1952, longer than I’ve been alive. I like things that stand up to the test of time and remain sweet no matter how many times we encounter them. I feel a tea party coming on. Hold the M&Ms.  The first lacey snowflakes drift past my window. They are the delicate advance men for a fierce nor’easter on its way. The anticipating world is already subdued. A forecast of snow brings with it a universally shared sense of caution. Go slow. Take your time. Tardiness will be excused. Don’t go out if you don’t have to. The snow provides a buffer against sound and activity. All is surreal. We watch the world, but are we in it? On such a day, the snow-covered earth is like an innocent bride in a gown of white while home is the church where children give thanks for snow-prayers answered. Staring out my window this morning, I feel the way I once did as a child living in the hilly suburbs of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was a time when the world had no problem sheltering in place. It was the average lifestyle. During the day, neighborhoods were devoid of traffic. Dads had the only cars with them at work. At home, Moms were busy with all of the hard labor of keeping house and maintaining large families. Kids went only where their feet could take them. Most businesses were closed on Sundays and there were blue laws. For school-age children, the lights went out by 9:00 PM, and the three television networks stopped broadcasting after the nightly news. Depending on the location, a ten or eleven o’clock public service announcement adjourned the day by asking parents, “Do you know where your children are?” We had a large bay window in our living room. On a snow day, that window was our weather channel. We were all budding Al Rokers, shouting weather updates from the sofa and providing special reports of kids sledding or cars skidding down our steep hill. When the snow accumulation became deep enough, we bundled up and went outside to play in the yard, throw snowballs, sled, or build snowmen. We might also shovel the area around the mailbox to make way for the postman or sweep the walkway to the front door for the paperboy and the milkman. My little brother, a budding entrepreneur by age 8, was quick to mow a lawn or shovel snow. He was born knowing how to make a buck. One winter, HB got his hands on a used snow blower. He made up little business cards offering services to the neighbors. He cranked out the cards on a small hand-held device that contained an ink-filled roller. In addition to my brother’s name and our home phone number, the cards listed his services including lawn mowing and blow jobs. We didn’t understand our father’s reaction to the cards, but they were confiscated and a new batch prepared with parental supervision. After hours spent outdoors playing, shoveling, and giving blow jobs, we came back inside through the basement, stripping off our ice-crusted boots and top layer of clothing. Clothing was hung on a makeshift clothesline where it could drip dry into the floor drain instead of all over the hardwood floors upstairs. We made hot chocolate from Nestle’s Quick which we all agreed would have been much better if only we had marshmallows. We spent hours playing Monopoly, and when that got old, we sleuthed with Nancy Drew, or helped to fold laundry. Snow days had the pace of a day one might expect in heaven. By nightfall, we were exhausted but happy. We paused in our home chapels to pray for more snow. Sometimes God heard us. More often, he took mercy on our mothers and gave priority to their prayers. He sent sunshine.  I heave a bag of raw chicken bones, skin, and fat into the open dumpster. The heat and humidity are oppressive cooking up a stench that permeates the air around the metal bin. As the bag lands atop the mountain of trash, a strong stink-bomb composed of the dumpster’s decaying contents explodes and shoots odiferous shrapnel up my nose bringing tears to my eyes. Another of my mother’s colorful expressions comes to mind: “That’s enough to gag a maggot.” Translation: “Gross!” But gross is in the nose of the beholder. The definition changes with each new stage of life. To a preschooler, bodily functions are gross no matter how many sweet or amusing names their parents give to urination, defecation, and human waste. Some little children master their fears and repulsion with potty talk. There is nothing like the four year old who cracks herself up as she works the words “pass gas” into every conversation or the kindergartner who makes farting noises with his hands at the lunch table leading to raucous behavior and time-out. Gross can be funny. However pleased with themselves, children know the management of gross is best left to grown-ups. By the time a person becomes a parent, the training wheels are off. It’s a master’s class starting with childbirth. With that behind us, we change diapers, empty basins full of vomit, hold gaping wounds together with one hand and steer the car to the emergency room with the other. We can forage through a teenager’s room that looks like a crime scene, empty the gym bag that contains the putrid remains, and go straight to the dinner table, appetite undiminished. Even adults without childcare duties face a not-so-handsome share of the disgusting. It is impossible to make it to mid-life without some experience with soft and furry compost mutating in the back of the refrigerator, clogged pipes in the bathroom, backed-up garbage disposals in the kitchen, volcanic sewer lines in the basement, road kill on the sidewalk, or pet droppings in the yard. By the time we round the bend toward retirement, we’ve seen stuff. Smelled stuff. HANDLED stuff. Our definition of gross has changed. We’ve kept company with the maggots. They might be gagging, but we’re not. At this stage, revulsion has nothing to do with smell or consistency. It has everything to do with embarrassment and shame. While we had our hands on the plungers and our eyes on the flies, social mores changed. It happens to every generation. It is part of the cycle of life, like maggots becoming flies. My grandparents were offended by pot smokers, free love, and men with long hair. Sorry, grandma, but weed is legal, love is easily found on the internet, and a man is likely to be sitting in the chair next to you at the beauty salon. Young people think older adults are prudes in decaying bodies. Old folks think young people are puppets in a decaying society. Topping my list of gross—the things that make me close my eyes and turn away, that make my heart fall and my stomach lurch: #1 – butts, thighs, side-boobs and other revealing selfies posted on social media accounts (Why?) #2 – far left or far right anything (What?) #3 - episodes of The Bachelor (Who, what, when, where, how, and WHY?) Once I catch even a glimpse of these things, it is hard to get them out of my head. And that stinks!  Today, I cooked butt. I will cook butt tomorrow, and the next day, and the next. It was a two-for-one sale. And it is not actually butt; it is shoulder. Pork shoulder. Only the label says butt. It must be the prime cut for people who don’t know which end is up. I guess they found me. During the pandemic, I asked my son to keep his eyes open for two-for-one meat sales at the grocery store figuring we could share. He’s super-busy. I’m not. In cave people style, I assigned the muscular, young adult male to find the meat and haul it home. The old, not-so-muscular-mom will tend the fire and do the cooking. Last night caveman delivered. In cavewoman style, I dragged the bag containing the two roasts across the kitchen floor to the refrigerator and heaved it onto the lower shelf. The bag was as heavy as a whole hog just not as squirmy. This morning, I cleared a countertop and got out the super-duper-sized crock pot. With another day of 100 degree temperatures, I won’t be firing up the oven and letting it run for eight hours. I carried one of the roasts to the counter and placed it next to the crock pot. “Houston, we have a problem.” This is one BIG butt. No way will it fit into the crock pot. Not even in Spanx. Minimalist that I am, I make do. I don’t own a meat cleaver, so I got out my favorite knife which is actually a tomato knife, and began to saw the hunk of meat in half. I thought I was doing okay until I hit bone. In the process I discovered how the butt bone is connected to the shoulder bone: I may have dislocated my shoulder or at least tore my rotator cuff sawing the butt in half. I persevered as cavewomen do. One surgically removed cheek of the butt roast is now in the crock pot the other back in the refrigerator. Three cheeks to go. I should finish by Sunday. Hopefully, that is enough time to rehab my shoulder. I guess I will have to establish some two-for-one sale guidelines. My son is a serious shopper ever on the lookout for bargains. He is also a powerlifter, so heavy is a relative matter. Hence my first rule: don’t buy anything heavier than your relatives. And if you happen to see a pair of bison--walk away!  Many years ago, during a lull between patients, my colleagues and I chatted. My co-workers were all women and accomplished healthcare professionals who had raised families. Their lives embodied success. One of the women asked the group, “If you could go back and relive one moment from your life, what would it be?” Without hesitation, all of the other women answered in unison: "a moment to rock my babies again.” At the time, my children were young school-agers, and I was a single mom just hoping to live long enough to see my kids grow up. Twenty years later, my children are young adults with busy lives, and I have joined the chorus. If I could relive a moment from my life, I would choose to rock my babies again. I would gladly take back the moments when my entire world fit into my arms, moments when no universe existed beyond my rocking chair. I would take back those eyes that sparkled like jewels inside a small, soft head covered with damp curls. I would breathe in the scent of those warm bodies exuding the fresh, clean smell of baby powder and innocent new life. I would take back those moments when their eyes locked with mine and a broad grin overtook their faces, droplets of milk escaping their cupid-bow lips and sliding down their small chins. I would delight once again in that moment of discovery and recognition, when their eyes danced saying: “It’s you! I know you!” And they were happy to see me. I would take back those sweet moments before the real challenges of parenting began, the moments before anything went wrong, the time before the universe expanded and the weight of the world was sometimes more than my arms could carry. Parenting is hard work. There are ups and downs. Personalities emerge along with needs, talents, and health problems. The adorable baby develops a mind and a will, and too quickly, our children enter a world outside our arms, a universe that is constantly expanding and often strange and frightening to us. All the while, we are also trying to manage the demands of work and adult life and the pressure to choose career over family. Books, magazines, newspapers, the internet, and social media inundate us with how-to advice and images of wealthy influencers as examples for comparison. We are constantly re-assessing and doubting ourselves. We are robbed of joy. If I were to write a book on child-rearing, it would be short: Parenting is hard work. It will not be easy. You will face uncertainty. Sometimes you will be scared to death. But nothing in your life—past, present, or future--will ever matter more. Ignore the mob and choose the joy. Stock up at the beginning. Savor the moments when the entire world fits into your arms and the universe is no bigger than your rocking chair.  The pandemic has shaken the world and dismantled our standard operating procedures. How will we safely re-open businesses? How will we get children back to school? How can we get people to wear masks? The experts weigh in and the politicians counter every recommendation. If the coronavirus doesn’t get us first, we will either worry ourselves to death or die from stupidity. When I was a child, in the nascent vaccine epoch, parents were more pragmatic. We lived through many childhood illness outbreaks. The standard, recurring diseases were rubella, measles, mumps, and chicken pox. Tonsillitis was common too. Thankfully, there were vaccines for small pox and polio and no reported cases of leprosy. Urgent care did not exist, and I never heard of an emergency room. When I fell on the playground and tore open the flesh on my knee, the school principal marched me over to the doctor’s office across the street, and Doc stitched up my leg. My parents got a phone call. When my brother got hit square in the eye by a speeding fastball, dad drove him home in the back of our Ford station wagon. Mom called the doctor, and the doctor made a house call later that evening. There were no x-rays involved, just a small flashlight and the doctor’s attentive eyes and clean hands. My brother recovered, and the pitcher went on to the minor leagues. One time I slid down the entire staircase from our second floor to the first, coming down so fast and hard that both of my legs went through the plaster wall at the bottom. I passed out. My parents heard the crash and came running. My father got me up and helped my woozy self to the couch. I could walk and talk. No doctor visit required. Never again did I attempt to climb the polished wooden stairs in slippery socks. The wall was patched and covered with a wall paper only slightly more attractive than the gaping hole. Back then, mothers, not ER doctors and pediatricians, were the arbiters of illness. They held the secret powers that determined if a child was truly ill and what, if any, medical care was needed. A mom could tell by looking at her child if the kid was sick or faking it. Maternal intuitive powers came from looking into her child’s eyes and checking the calendar and the homework. If a test or a particularly unpleasant unit in gym class was scheduled that day, a child could do her best acting, but she was unlikely to get past the MRI--mother receiving information. Unless you were in a full blown grand mal seizure, a fever was the hallmark sign of illness. It was a child’s only hope of being taken seriously and staying home from school. A seizure would pass and wasn’t contagious. You might find yourself getting to school a little late. In this age of coronavirus, we have new-fangled, high-tech, instant, non-contact, digital, infrared thermometers. That’s a lot of power to hold in your hands! When I was a child, moms didn’t need thermometers. A mother would tenderly place her palm or cheek across her child’s forehead, feeling the heat, Mom would determine the presence of fever…or not. If Mom had any doubt or wanted to validate her findings to provide the school principal with actual data, the mercury thermometer came out of hiding. Mom would shake, shake, shake the thermometer and then slip it under my tongue. I had to sit with my lips tightly sealed for at least a minute. People are too impatient for such devices now, and that is far too long to keep your mouth shut in 2020. Minor injuries were taken in stride. A sprained ankle meant time on the couch with a leg elevated and a homemade ice pack attached to the injury with an old, soft bath towel. There was usually a used crutch somewhere in the basement that could be called up for duty if hanging onto the furniture was insufficient for mobility. Today, a teen would go into the emergency room and come out with a handful of opioids. Other home remedies were applied in this era before big pharma. Despite my mother’s oft-stated social commentary, “That gives me a pain where a pill can’t reach,” there weren’t that many pills from which to choose. Chief among the maternal prescriptions was rest on a comfy couch. Other interventions included baby aspirin, Vick’s Vapo-Rub, and cartoons. Weak tea and cinnamon toast delivered to the couch along with some soft kisses on the warm forehead rounded out the treatment plan. Occasionally, the interventions were unique to the disease. I can remember that my siblings and I wore diapers around our faces when we had the mumps. What was that about? Perhaps it was intended to be a badge of honor, the uniform of a stalwart soldier battling inner suffering. Even so, I’d rather wear a mask. A few times during my youth a child did disappear from the classroom for an extended period of time. Occasional serious illnesses or surgeries that required hospitalization did occur. A kid could miss months of school as surgeries were more invasive and complicated, alternative treatments far fewer, medications more limited. Recovery times could be lengthy, stretching into months. Sometimes a fellow student did not return to school for the remainder of the year. There were no computers or high-tech devices connecting classroom to home. The youthful patient used an actual book to self-educate. No parent was going to spend an entire day every day “home-schooling,” but older siblings or parents were willing to be the go-betweens, exchanging assignments between home and school. If necessary, children repeated the year of school and everyone understood. It was a reasonable option in extreme circumstances. With one foot in the past and one in the present, I would rather wear a mask on my face than that old cloth diaper around my head. And most definitely, I prefer either of those face coverings to a ventilator. Books and pencils along with thoughtful assignments, some self-discipline and a little monitoring can go a long way in the absence of technology. Women sent men to the moon with their good minds, a few books, and pieces of chalk. Nothing will be lost if a living, healthy child spends an extra year in school when the pandemic is over. And if you wake up and want to know if you have a fever, call and ask your mom…if you are lucky enough to still have her. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

April 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed