all of the selves we Have ever been

It’s that time of the year. The temperature goes up and down giving us four seasons in a single day: cool fall mornings followed by spring-like afternoons, the heat of the summer sun in the evenings turning into early and frigid winter nights. All of this temperature fluctuation causes an orange light to glow like a Halloween jack-o-lantern on the dashboard of my car. I admit it. It spooks me. Each time I see the light, I do a slow burn. Like a candle melting down into a pumpkin head, I wither with despair. Sweating it out in this ring of hell, I have a fleeting moment of understanding. Perhaps this is the thing that put the anti-maskers and the anti-vaxxers over the edge, making them militant against any new safety mandates. Yes, the anti-safety movement may have begun with the TPMS light. Against my will, I was dragged into the Trial Purgatory Membership Service. Don’t let the word “trial” confuse you. It does not mean a brief introductory period. It means ordeal, the actual ordeal of purgatory. You get to work off your sins and reduce the waiting time at the pearly gates while you go about life on earth. The program is open to any licensed driver who purchased a vehicle manufactured after 2007. I did not understand this when I bought my 2009 Hyundai Elantra. I inadvertently signed up for the TPM Service. It was automatic with purchase. Some might call it a perk; I call it hell on wheels. The program is relentless and has turned my car into a time share. I spend the start of every outing searching for “free” air which is getting harder to find. I am more obsessed with my PSI than I am with my blood pressure which rises a little higher every time I see the light. The TPM Service is not just in charge of the tires, it has become like a parole officer setting limits on my freedom. At this time of the year, the light comes on so frequently that I try not to drive. I suspect the TPMS is a real boon to Uber, Lyft, and restaurant delivery services. The rise in agoraphobia among licensed drivers may have more to do with the TPMS than with the global pandemic and lockdowns. I am traumatized each time I start the engine and see the light glowing from behind the steering wheel. In the rare instances when I am forced to take to the road, I survey each tire before opening the car door. I say a prayer that I can sneak in the door and start the engine, without the light coming on. But with its ability to measure air loss within a single molecule of change, the TPMS usually outsmarts me. I dread the day the air pump manufacturers catch on and begin to charge us for air by the molecule. With the TPMS light on, I drive the side streets reassuring myself that the both I and the car will be safe until I get to an air pump. It is when the light comes on while driving down the interstate that panic sets in. I have discovered that if there is radar in the area, the TPMS light may come on without any real relationship to the air pressure in the car’s tires. Apparently, in purgatory, police cruisers and truckers are allowed to torment you too. A friend suggested tape. “Just cover the warning light,” she said, but that measure only makes me feel worse. My mind can’t rest. It’s like coming home alone and thinking that a serial killer is hiding behind the shower curtain. This forces me to gamble with my life. All I can think about is what’s behind the tape. Is the light on? Is it off? I become a distracted driver, and I don’t even own a smart phone. I have a smart aleck for a car. I will tell you from experience--don’t bother trying to call the Trial Purgatory Membership Service. All of its representatives are busy. All of the time. I have since learned that the company rocketed to billionaire status and fame with an earlier invention: the phone menu. Right now the entire customer service staff is on the company’s space station growing weed and working up an appetite for their next sneaky venture. Who knew the evil that could lurk in the hearts of men with technology? Unfortunately, we consumers are left spinning our wheels. Getting out of the Trial Purgatory Membership Service will take an act of Congress, and, well, they aren’t getting much work done. I am beginning to suspect that they are all on the TPMS Board of Directors.

0 Comments

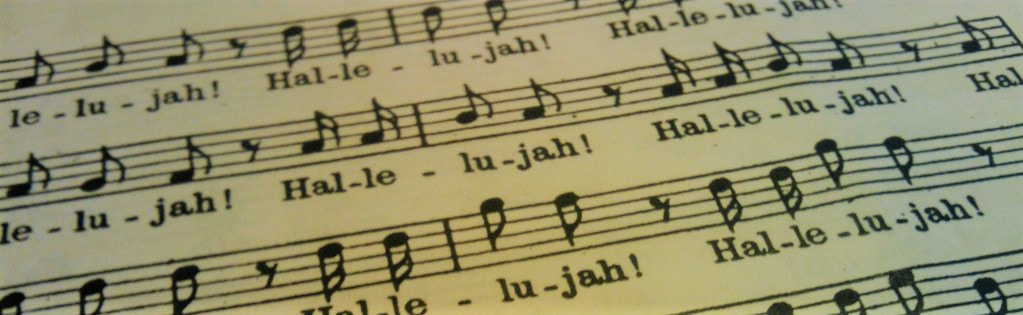

It’s eight o’clock on a Friday. The out-of-town crowd shuffles in. There’s an old friend sitting next to me waiting for the show to begin. She says, “I hope he plays me some memories, something I’m sure how it goes, the sad and the sweet that I knew complete when I wore a younger girl’s clothes.” Then he says, “I’ve got nothing new to play for you,” and the crowd whistles and cheers with delight. We agree it is sweet that we know them complete ‘cause that’s what we came for tonight. It’s a pretty good crowd for a Friday and every face young and old has a smile because it is he that we came here to see to forget about life for a while. He sings us his songs our piano man. He sings us his songs all night, and we’re all in the mood for his melodies. It is time for some things to feel right. The atmosphere is a carnival as the crowd slowly sips on its beers, and we sit in the stands and clap with our hands, and say, “Man it is good to be here!” And then, just like that, it is over. We wait for Brother Joel to return. And he steps on the stage with an encore arranged, and he plays ‘til a new day is earned. On the eve of 9/11/2021, the 20th anniversary of the attack on the World Trade Center, I attended a revival. Our tent was the Great American Ballpark on the banks of the Ohio River. Take me to the water! The leader of this traveling salvation show was not a preacher. He was a musical storyteller, a piano man. We arrived to the event weary and worried, pulling ourselves from the rubble of a global pandemic and reminders of the life-shattering events of 9/11. Then the Piano Man stepped onto the stage. He put his hands on the baby grand, and we were all born again. He rocked us awake from our COVID sleep and out of our painful 9/11 nightmares. His old songs became our medicine, pain relief in a time capsule, taking us back to simpler days and better places: high school dances and college dorms, first concerts and first loves, songs on the road and songs in the shower, the ages of vinyl, cassette, and CD. There was joy and happiness, togetherness and hope. In a crowd of thousands, each person sang from the same page in a shared and familiar songbook. Bass or soprano, alto or tenor, it didn’t matter. There was harmony. The Piano Man delivered the sermon in lyrics as familiar and reassuring as old psalms. By the time the night was over, we were all converts. Rising from the ashes of our sorrows, we found that we could survive the burns. Hallelujah! On the eighth day, after some rest, God said, "Let there be music." And there was. He sent us a piano man. 'Cause even God's in the mood for a melody. He wants us feelin' all right.  In the midst of a pandemic that feels endless, already there is talk of the next crisis--water. Knowledgeable people are banking on it, trading water on the commodities exchange. News footage validates the forecast with images of dry river beds, massive wildfires, and places where critical ground water has been pumped beyond its limits to replenish. Waterways are polluted by industrial toxins, discarded plastics, and human waste. Around the world, people are on the move leaving behind land that is turning to dust. I sit here in my uneasy chair for some self-examination. I have taken the supply of water for granted my entire life. I turn on the tap and out flows cool, clean water. As a teenager living in the growing suburbs of Pittsburgh, I became familiar with families living outside the city limits whose homes had wells. Sometimes I visited them in the summer when the water was low and laundry had to be hauled to the laundromat, and the grass turned brown, and showers were limited to keep the wells from running dry. It all seemed so primitive to me from my perch in the privileged suburbs where the sprinkler ran for hours. In my mind’s eye, wells belonged in the old American west, to a world of gunslingers and dusty cattle drives, in barren places depicted on shows like Rawhide and Gunsmoke, a world of black and white, certainly not living color. Earlier experience had led me to this faulty conclusion. There were two giant concrete discs in my grandmother’s grassy backyard. It was only in fleeting moments of bravery that I dared to run across one of the discs. More often, I walked around them fearing that something dangerous lurked beneath and was just waiting to grab me by the ankles. Perhaps it was our happy lives above ground that skirted trouble from below. Above the ground life was vibrant. Children laughed while grabbing juicy pears from the tree overhanging the porch. Aproned women snipped dewy roses from thorny bushes that climbed white trellises along the back wall. Damp clothes hung shoulder-to-shoulder on the clotheslines, shooing away danger as they blew and snapped in the swift summer breeze. Screen doors slammed as we ran in and out of the house. Familiar voices filled the air like music. Somewhere along the way, I learned that the concrete discs in my grandmother’s yard were lids. They covered the cisterns that once upon a time collected rainwater to support life and clean laundry inside my grandmother’s house. I was dumbfounded. I never imagined that the ultra-modern home of my grandmother had a frontier history. How could that be when every modern innovation in the world was introduced to me there: wall-to-wall carpeting, automatic dishwashers, recliner chairs, color TV, and air conditioning? Clearly, gathering rain water was ancient history. Problem solved. We were modern taps and pipes people who relied upon the city water department to do the heavy lifting and keep the river of water flowing into our home. The magical innovations that appeared inside my grandmother’s house were not only evidence of a changing infrastructure, but evidence of a changing thirst, and we, like many Americans, became insatiable. We wanted more of the new, the time-saving, and the convenient. The economy was booming in the post-war era and so were the number of babies. Life had been hard. Now it was good. It was easy to believe that the frontier days of wells and cisterns were a thing of the past. We never imagined that water itself would disappear in our quest to make life not just easier, but effortless. We grew up as descendants of the American frontier and were fortunate to bring our children into a world of abundance and convenience, but our children face life on a new frontier, the frontier of climate change. Will their lives be better or more difficult than ours? As I downsize, focusing on what to keep and what to leave behind for my children, I look at my stuff and realize that I have never owned anything more precious than water. If I could do it all again, I would trade automatic dishwashers and color TVs for the life that existed in my grandmother’s backyard. I would buy insurance so that my children would be sure to know the cool, soft pleasure of moist green grass between their toes, the sweet flavor of pear juice trickling down their chins, the musky fragrance of velvety roses tickling their noses, and the sound of damp, clean clothes snapping in the breeze shooing away danger. I would have lifted those lids and saved for my children an inheritance that is the birthright of all children, the life-giving, thirst-quenching miracle that is water.  If you want to go fast, go alone, but if you want to go far, go together. – African Proverb ******************************** Speed is the thing. It is the only thing. We want express lanes and speedy deliveries, fast food and speed dating, prompt responses and high-speed internet. We prefer snap judgments and quick reads, fast-acting elixirs and rapid relief. Forethought and careful attention to detail are as extinct as dinosaurs. Demand either today and your age is showing. And your new name is Karen. You will be tossed into the category of emotional extremist faster than you can swallow your dignity. Accuracy is not to be factored into the results so long as we are going as fast as we can. Destination is superfluous. In the prescient words of Yogi Berra, “We’re lost, but we’re making good time.” Here is the latest example. My friend Angie placed an Amazon order. Within the promised hours, Angie’s phone pinged an alert. The delivery driver was eight doors away. Angie waited a few minutes and then opened her front door. Ta-da! Prime magic. A package had appeared on her porch. Puzzled by the size of the box, Angie picked it up and studied the shipping label. The name and address belonged to a neighbor. Suspecting a mix-up by a harried delivery driver with a full bladder, Angie carried the package to the neighbor’s house. Sure enough, the package intended for Angie was on the neighbor’s porch. Fearful of being mistaken for a porch pirate, Angie knocked and traded parcels with her neighbor. Back home, Angie opened the box and removed the paper, the bubble wrap, and the plastic shrink wrap. Through some sleight of hand, the item in the box was not what Angie had ordered: wrong address, wrong item, but “on time.” There is some black magic that I can’t comprehend. Speed has been separated from time and results. Age may be a factor in my befuddlement, but age seems like a convenient stereotype to explain away this turn of events. I find myself looking for speed bumps, something to calm the traffic and prevent accidents. Many of us are just not fast lane people. We never were. We obey the speed limit, brake for squirrels, read the road signs, slow down and let others merge. We study the billboards and mentally correct the grammar, memorize the faces of missing children, ponder the Bible verses, and take note of the new businesses. If a caution sign says work area ahead, speed limit 50 mph, we’re willing to risk our lives for the sake of others. We…slow…down. Growing up in a different era reinforced my already unshakeable predisposition to travel in the slow lane. “Pay attention” was the theme song of my youth. We painstakingly practiced penmanship and served time in detention for running in the hallways at school. Adults were there to borrow from John Wooden and remind us: “If you don’t have time to do it right, when will you have time to do it over?” We lived a life of lazy Saturday mornings lounging in our PJs until noon. We spent Sunday afternoons our grandmother’s house when all the shops were closed and a family dinner took all day. We were encouraged to slow down, take our time, do things right. The only thing we were in a hurry to do was grow up, and my mother warned us about that, too: “Don’t wish your life away.” Perhaps she was influenced by Shakespeare’s Macbeth who warned us of the “brief candle” that is our lives. Now, after a lifetime of temperament and conditioning, I find myself pressed to choose speed over satisfaction, action over forethought, frantic energy over peace of mind. Shoot me an acronym-filled text message, there’s no time to talk. Or listen. Life is zipping away. I can’t help but wonder, are we really saving time with all of this speed? If so, what is everyone doing with all of the extra time? Collapsing from exhaustion? When our loved ones travel or begin a new adventure, we wish them God speed. God speed is a blessing, not a curse. It is a prayer that the traveler will arrive, not swiftly, but safely and well. God speed implies fidelity, an old word meaning faithful and true. The right package reaching the right house at the right time in the right condition for the right reasons to serve the right purpose. I wasn’t built for life in the fast lane, and I don’t like going it alone. I find the journey safer and more enjoyable when I share the road with others. I am older now, but I still have far to go. I want the journey to be for the rights reasons and serving the right purpose. Will you come with me? We’ll go together. At God speed.  A nurse met me at my office door: “Can you keep Stella company? Her mother and brother are in with the doctor.” “Of course!” How could I say no to a child? The petite preschooler let go of the nurse’s hand and approached the office chair across from my desk. The chair must have looked like a mountain, but without hesitation or request for assistance, Stella succeeded in the climb. Once in the seat, she turned to face me. Bracing her hands against the arms of the chair and mustering all of her strength, Stella extended herself into a full body stretch. With her feet planted against the seat and her back arched, it seemed she might make herself large enough to fill the giant chair. Despite all of that effort, the heels of her black patent leather shoes did not reach the edge of the seat. Stella centered herself on the roomy cushion, smoothed her skirt, and gracefully crossed her legs at the ankles. Narrow bands of lace adorned the cuffs of her tiny white socks. Stella placed her hands in her lap and looked straight into my eyes. “Why have you come to the clinic today, Stella?” “It’s my brother. He’s resturbed.” Stella spoke earnestly, like a concerned colleague providing a case review. I felt a sting in my chest. This precocious child should have been at home watching Sesame Street and memorizing the words to nursery rhymes. Instead, she was hanging out in a mental health clinic and learning the jargon of psychiatry, the words necessary to explain the odd thinking and behavior of a six year old brother with schizophrenia. The condition ran in her family; Stella’s mother was “resturbed,” too. Thoughtful in her every move, Stella seemed intent on distancing herself from the condition that held her brother and mother captive. Stella and I shared a few moments on a busy morning long ago. Now, I am the one trying to cope with the fear and chronic fatigue that comes from living in a world gone mad. Symptoms of severe mental illness have spread faster than the coronavirus: poor reality testing, delusions, chaos, confusion, suspiciousness, prolonged anger and hostility, lack of insight, poor judgment, increased violence, rigid thinking, poor impulse control, hypersexual speech and behavior, excessive anxiety, peculiar beliefs, inability to form or sustain close relationships, self-importance and attention-seeking, inability to consider the needs of others…Many days it is a struggle to hope, to believe that the world is not irretrievably broken. That is when I think of her. How did Stella do it? Despite her growing awareness of the mental illness that surrounded her, that tiny, precious child was still so innocent, so whole. She was graceful and well-mannered, intelligent and articulate. She waited patiently for the experts to do their work, and she followed their advice. Somehow, she remained capable of trust. Stella gave maximum effort to taking the seat assigned to her. It didn’t matter that the seat was too big; she sat up straight and tall and held on to her dignity. Though it took effort, Stella stretched and planted herself firmly in the middle of the space afforded to her. Character added to her beauty; she was the delicate lace around the rough edges of life. Stella was brave enough to hear the truth and to tell it to others. She was cautious but open. Stella could separate herself from the odd behaviors of her people and love them anyway. She was willing to make the effort to be extra good, to help balance the cargo so that her capsizing family ship did not go under. And somehow in the chaos, she found what she needed to grow and develop. Like Stella, many us are feeling weary and outnumbered. We are trying to be extra good to balance the load, to find what we need to sustain ourselves, but the problems seem so big and so numerous. Leadership is, at best, disappointing, at worst, terrifying. Each day brings something new and disturbing. I have been disturbed so many times that maybe that defines me as “resturbed,” too. I long for peace, the restoration of dignity, the practice of common courtesy. I want the world to work again. I don’t think we can count on politicians to get us out of this crisis. I do think it will take another epidemic, an epidemic of decency--simple, persistent, contagious goodness. Perhaps a child should lead us. Are you out there, Stella? |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed