all of the selves we Have ever been

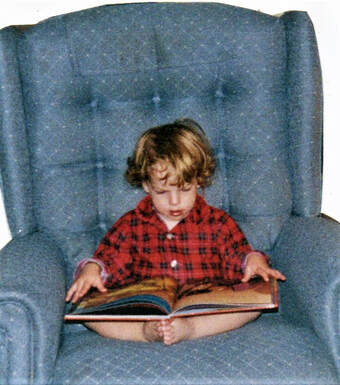

I thought they were for old people. More specifically, for grouchy old men. It was a dad’s chair. Dads became grouchy when other people tried sitting there. But then I became pregnant with my first child. Anemia, heartburn, and sciatica became the side effects of an average, fist-sized uterus stretching to accommodate a growing 10 pound 2 ounce baby girl. Altogether, it was a recipe for insomnia. My obstetrician suggested a recliner chair. But I was only 34. And female. Destined to be a mom, not a dad. The medical science did not compute with the cultural anthropology. But a pregnant woman needs her rest while she can get it. So it was off to the La-Z-Boy store. We settled on a soft, cloth-covered version of the recliner that came to be known in our home as thebluechair. It was the preferred seat of everyone. If you were ever a guest in our home, you sat there. If you were ever photographed in our home, you were probably sitting in thebluechair. One or both of the children were likely snuggled in beside you. thebluechair was a magnet. Even little children loved thebluechair. It didn’t hurt that thebluechair was aimed at the TV. This is the arrangement recommended in the set-up guide for all TVs and recliners – they MUST face each other. Your warranties will be voided if you violate this rule. I suggest that if you are having trouble with your TV reception or your comfort that you check your room arrangement BEFORE you contact the retailer. Television, La-Z-Boys and inertia all grew up together in the 1950s. They have an inextricable bond. If you have things to do, do not, I repeat, DO NOT sit down in a recliner chair. Physics will not be on your side. I was introduced to the recliner chair in my grandparents’ home and later in the homes of wealthier aunts and uncles. It appeared to be some type of throne. I knew my family had moved up in the world when a recliner chair appeared in our more humble abode. While it was a grown-up chair, it did serve a child’s imagination. Some days it was a rocket ship. That giant side-lever launched a few of us into space. Other days, in its fully-reclined position with an afghan thrown over it, the chair became a cave. One day, quite unexpectedly, little spelunker-me made a giant discovery. I struck gold! Literally. And I learned something more about physics. The same gravity that glued butts to the seat also forced change out of dad’s pockets and into the mechanical compartment underneath. Ever after, I was happy to volunteer to clean the living room on Saturdays, the day for chores in our family. Somewhere between striking gold in the cavern of dad’s recliner and purchasing my latest chair, I did some research. Ancient Greek Gods and Goddesses liked to spread out on daybeds called “klines.” Later, reclining furniture would be extolled as a health aid. In the La-Z-Boy corporate publication on the history of the recliner, the development of the modern La-Z-Boy in 1928 is described as “a momentous event in relaxation.” That’s truth-in-advertising. I can confirm that every time a La-Z-Boy has entered my domain, it has been a momentous event in relaxation. My obstetrician may have been old school and studied with Alexander the Great, but he was right about the recliner chair. It was a sad day in our house when thebluechair finally wore out and went to the curb. Even the children cried, “Oh, no! Not thebluechair!” In our family, the La-Z-Boy is no longer the chair of grouchy old men and laid-back dads. It is the best seat in the house for everyone.

0 Comments

A neighbor stops in: “Oh, your house is so clean!” At my stage of life, which is just inches from the grave, I can’t risk the threat of eternal damnation by being a fraud: “Well, there’s order, but I wouldn’t say it’s clean. That’s not sheers on the windows.” I survey the rest of the room eyeing dust on the shelves so thick that it looks like starched doilies. I grew up in an era when an entire multi-generational family was judged by the quality of one woman’s housekeeping. In those years, my neighbor would not have gotten past the front door. My mother would rather have been seen in the shopping mall with curlers in her hair than to let an outsider see our dingy windows and dusty shelves. Hence, housework became my default occupation. I never applied for the job. I was drafted against my will by virtue of being a kid, a girl-kid, and living in a house. There was no lingering suspense to the draft process. There was no multi-million dollar contract, not even an allowance! I was not offered a name-and-likeness-deal. I did not even get a t-shirt with my favorite number. Once a baby girl could stand on two feet and hold a soft rag, she was signed up. I didn’t get to choose my team, otherwise, I would have picked Agnes’s house down the street where the rooms were arranged like art exhibits. All of the furniture was covered in plastic and no one was allowed to enter those museum-like spaces. Saturdays were game days all over America. While most of us lived in smaller homes back then, about 1100 square feet, every inch was crammed with people—six in our house, along with a dog and a couple of neighbor kids who appeared to be orphaned. Despite the crowd, there was only one bathroom which was also typical of that era. Every space was over-crowded and over-used. To do a good cleaning meant every piece of furniture and every stationary person had to be moved down the field, cleaned, and returned to the starting line. One of the younger kids was constantly being displaced on cleaning day, chased from one room to another. They were out of bounds wherever they landed. Of course, the work-out didn’t end when I got my own place. By then, I was well conditioned, hooked on Spic ‘n Span, and a psychological prisoner of the vacuum cleaner. A weekend could not go by without a darkened dust cloth and the smell of lemon Pledge. As a mother, the duties expanded exponentially. Now with the children grown and out of the house and full time employment behind me, I am getting out of the inside game. I will give housework 15 minutes at a time. That’s my limit. Even young, hefty, well-conditioned football players get a pause every fifteen minutes, and so I head to the bench for a water break, to nurse my injuries, talk with my team mates, connect with the audience, and see how things look on TV. Between games I’m happy to study the play books. I‘ve got a stack of House Beautiful magazines. I consider them a kind of pornography for the housekeeping derelict. It all looks slick, salacious, and out of my league. I am convinced that it must be illegal. It’s a new season. Here on the fourth down of the final quarter, I punt. Let a new team carry the dirtball.  In the midst of a pandemic that feels endless, already there is talk of the next crisis--water. Knowledgeable people are banking on it, trading water on the commodities exchange. News footage validates the forecast with images of dry river beds, massive wildfires, and places where critical ground water has been pumped beyond its limits to replenish. Waterways are polluted by industrial toxins, discarded plastics, and human waste. Around the world, people are on the move leaving behind land that is turning to dust. I sit here in my uneasy chair for some self-examination. I have taken the supply of water for granted my entire life. I turn on the tap and out flows cool, clean water. As a teenager living in the growing suburbs of Pittsburgh, I became familiar with families living outside the city limits whose homes had wells. Sometimes I visited them in the summer when the water was low and laundry had to be hauled to the laundromat, and the grass turned brown, and showers were limited to keep the wells from running dry. It all seemed so primitive to me from my perch in the privileged suburbs where the sprinkler ran for hours. In my mind’s eye, wells belonged in the old American west, to a world of gunslingers and dusty cattle drives, in barren places depicted on shows like Rawhide and Gunsmoke, a world of black and white, certainly not living color. Earlier experience had led me to this faulty conclusion. There were two giant concrete discs in my grandmother’s grassy backyard. It was only in fleeting moments of bravery that I dared to run across one of the discs. More often, I walked around them fearing that something dangerous lurked beneath and was just waiting to grab me by the ankles. Perhaps it was our happy lives above ground that skirted trouble from below. Above the ground life was vibrant. Children laughed while grabbing juicy pears from the tree overhanging the porch. Aproned women snipped dewy roses from thorny bushes that climbed white trellises along the back wall. Damp clothes hung shoulder-to-shoulder on the clotheslines, shooing away danger as they blew and snapped in the swift summer breeze. Screen doors slammed as we ran in and out of the house. Familiar voices filled the air like music. Somewhere along the way, I learned that the concrete discs in my grandmother’s yard were lids. They covered the cisterns that once upon a time collected rainwater to support life and clean laundry inside my grandmother’s house. I was dumbfounded. I never imagined that the ultra-modern home of my grandmother had a frontier history. How could that be when every modern innovation in the world was introduced to me there: wall-to-wall carpeting, automatic dishwashers, recliner chairs, color TV, and air conditioning? Clearly, gathering rain water was ancient history. Problem solved. We were modern taps and pipes people who relied upon the city water department to do the heavy lifting and keep the river of water flowing into our home. The magical innovations that appeared inside my grandmother’s house were not only evidence of a changing infrastructure, but evidence of a changing thirst, and we, like many Americans, became insatiable. We wanted more of the new, the time-saving, and the convenient. The economy was booming in the post-war era and so were the number of babies. Life had been hard. Now it was good. It was easy to believe that the frontier days of wells and cisterns were a thing of the past. We never imagined that water itself would disappear in our quest to make life not just easier, but effortless. We grew up as descendants of the American frontier and were fortunate to bring our children into a world of abundance and convenience, but our children face life on a new frontier, the frontier of climate change. Will their lives be better or more difficult than ours? As I downsize, focusing on what to keep and what to leave behind for my children, I look at my stuff and realize that I have never owned anything more precious than water. If I could do it all again, I would trade automatic dishwashers and color TVs for the life that existed in my grandmother’s backyard. I would buy insurance so that my children would be sure to know the cool, soft pleasure of moist green grass between their toes, the sweet flavor of pear juice trickling down their chins, the musky fragrance of velvety roses tickling their noses, and the sound of damp, clean clothes snapping in the breeze shooing away danger. I would have lifted those lids and saved for my children an inheritance that is the birthright of all children, the life-giving, thirst-quenching miracle that is water.  A friend of mine lives in a suburban neighborhood where the wildlife is becoming too friendly, some might even say BOLD. Despite repeated attempts to discourage them, the groundhogs have taken up residence underneath decks and porches and the deer walk right up to the front doors and ring the bells. The family pets do little to deter the wildlife, and that includes a pet pig that can moonwalk on command. It appears that the animals have taken up the lives we used to have. My friend spent the first half of the pandemic trying to woo a groundhog out from underneath her back deck and then keep him out. Since I am not sure where all of this is headed, my friend shall remain anonymous. Let’s just call her Q. Q began her interventions by placing a small fence around the groundhog’s front door. To no avail. The groundhog simply dug a bigger hole and went underneath the fence. Next, Q piled small stones around the entrance to the tunnel, but the creature moved the stones to the side, crafted a pair of gargoyles that looked remarkably like my friend, and went on inside. Q thought the natural animal fear of a predator might work. Q got a large plastic owl and placed it at the entrance. The groundhog knocked the owl over, slapped it to the side, and spit on it before regaining entry to its groundhog digs. Giving up on barriers, Q then tried appealing to the groundhog’s senses. Q sprayed the area with ammonia. Again, to no avail. Perhaps, the scent was no worse than the typical smells of a groundhog home. Q also tried sprinkling cayenne pepper at the entry, but it appears that the creature preferred life spicy. Shiny, spinning pinwheels were no distraction and may have been enough extra wind power to provide electricity to the underground tunnel. Q tried sleep deprivation as a discouragement strategy and kept bright lights focused on the groundhog’s home night and day. Q was pretty sure she heard the groundhog laughing at her. Desperate, Q left the groundhog a written notice of eviction and posted a Keep Out sign at the entrance to the hole beneath the deck. Q later found a tiny pair of reading glasses in the snow. The Keep Out sign was turned around with the words Live, Love, Laugh printed on the back. There was no response to the eviction letter. Q then sprinkled baking soda around the deck to track the groundhog’s footsteps so that she would know when it left the tunnel and which direction it had gone. While the animal was out, she backed up the truck and filled the area with large rocks. Q says she hasn’t seen the groundhog since, but Q has no will left. If Q sees signs of the groundhog’s return, she plans to declare him a dependent on her income tax return. Now the neighborhood is getting together on a Zoom call to discuss the deer problem—upping their game so to speak. My friend is eager to hear what the neighbors have to say. This has me worried. We are all a little on edge given the politics, the pandemic, and the weather. I remind my friend of the lyrics to that old folk song, Home on the Range: …where the deer and the antelope play…never is heard a discouraging word and the skies are not cloudy all day. We need that… but I think it might be too late.  When everyone you love leaves the building, is it still Home? I experience uneasiness when my adult children visit the house and then leave. I become keenly aware of my aloneness. I feel restless and conspicuous, a stranger in my own dwelling. I am like the lone diner holding a big table in a busy restaurant. Self-conscious and out-of-place, my mind obsesses: Everyone’s late. Will anyone come? Have they forgotten? Has something terrible happened? Should I call? How long do I wait? Should I stay? Should I go? Do I order? What if they never come? After a day or two, I fall back into the rhythms of my daily life, but it starts all over again the next time the children visit and say goodbye. The writer Thomas Wolfe wrote You Can’t Go Home Again. Well, you can go home, but maybe you shouldn’t, at least not when the house is no longer occupied by people you love. A few years ago, I visited a friend in Pittsburgh. I had not been back to my childhood hometown for more than 20 years. I had not seen the family house in more than 30 years. My dear friend who understands these things offered to drive me past the home where I spent most of my childhood. I still remembered the address, and was able to navigate our way to the neighborhood even though I could not recall the name of every street we traversed to get there. We pulled up alongside the old two-story house. It looked small and dingy. Was the yard always that tiny? How could that patch of grass have hatched so many games and adventures? How did we have room for baseball, hide-n-seek, running through the sprinkler, and chasing lightning bugs? The stocky, bright green pine trees my father planted along the driveway were now giants but they looked dark, scraggly, out-of-place, and menacing. A strong wind might bring them crashing down on the house. I wondered, “Who lives here now?” Does the old house seem so weary to them? Or is it a “new” home to someone? Are children inside fighting over the remote and laying claim to the couch? Is there still a chain lock on the basement door that someone checks as they close up for the night? Who is sleeping in “my” room? Does wallpaper still cover the place where my feet went through the wall after I fell down the wooden steps in my stockinged feet? Is there a dad listening to talk radio in the basement workshop? Are a couple of boys out in the backyard building rocket ships out of cardboard wardrobe boxes? We sat in the car for a few minutes. No signs of life emerged in or around the house. It was a corpse, and I felt bereft. Seeing my former home so changed seemed to be sucking the life out of me. It was time to get out of there. I can’t go back again. I should have known better, but when I visited my cousin Marcia at her home in Cadiz she asked me if I wanted to take a drive to Adena, the family home of my mother and our maternal grandparents. It was the most magical place of my entire childhood, maybe my entire life. I had not been back for a very long time. “Let’s go,” I said. We drove down the main street past the old office of my uncles’ coal company. Further down the street on opposite sides, the house of my Aunt Addie was inhabited by a new family I did not know. Across the street, my Uncle T’s house had gone through several transformations. It had been a doctor’s office and then a residence to someone new. Neither house was as grand as I remembered. No light or life beckoned me to enter the front door or run around back to the playhouse or the basketball court. The real heartbreak was yet ahead. We turned onto Hanna Avenue, the yellow-brick-road of my childhood. It led to the family grocery store and to my grandmother’s house. Where there had once been a door that squeaked open and slammed shut hundreds of times a day, an empty lot greeted me. The store had been torn down years before after being used for a training exercise by the fire department. The grand, old house was standing, but barely. It leaned toward the street looking flimsy. After the passing of my grandmother and my aunts, the house was sold to a woman who planned to establish a home for elderly folks in need of care. The plan did not come to fruition, and the bank now owned the home with plans to demolish it. I longed to enter one more time, to walk the long hallway, sit down in the bright yellow kitchen, to take some kielbasa from the skillet on the stove. But the lights were out. Not just in the house, but in my eyes. I blinked. Stared. Blinked and opened my eyes wider. Nothing. Something changed in my heart. I felt robbed. It was like being part of a black-and-white pencil sketch instead of a colorful, three-dimensional world. There was no background. No sound. Everything was vague and disappearing. The past was being erased. There is no Home to go back to. I think of Homer’s epic tale, The Odyssey, the story of Odysseus’s journey home after the Trojan War. It took Odysseus ten years, of wandering and being tested. For seven of those years, he was in captivity, mourning and dreaming of home. We are in the midst of a pandemic. First, it was characterized as a battle, then a storm. Perhaps, for most of us, it is the epic journey of our lives. We dream of Home—not just the shelter where we hang up our coats and lay down our heads for the night, but the place where we visit and entertain, where we freely embrace our loved ones and watch the children and grandchildren grow up. It is the place where we share hugs, kisses, and joy not germs. This holiday season, we are all dreaming of Home. I have safe shelter, but that alone is not Home. I am reminded of the definition of Home every time my children visit and say goodbye. Wherever they are, that’s my Home.  There are some stains we treat and scrub. We want them OUT. But there are others that become part of the fabric of our lives. Unexpected souvenirs of people, times, and experiences we cherish. We want them to remain FOREVER. I began the day searching for my light gray sweatpants, the ones with the white paint stains on the knees. My Saturday clothes. I had things to do. The paint stains are a happy reminder of living in Missouri and helping a friend to prepare his new home for move-in day. It was a different Saturday as we stirred paint, filled trays, and loaded the rollers. We worked across the room from each other sharing stories and anticipating the new life my friend would have in the freshly painted rooms. A year later, I would bring a little of my friend with me when I returned to my home in Ohio. The stains on my sweats remind me of that pleasant paint-filled Saturday and a kind and faithful friend. As I prepare my breakfast, I see the blue and white enameled butter dish with the worn finish. A hint of rust hides under the lid. The loop of a handle has a dark spot where I place my thumb. I imagine my grandmother holding this butter dish in her hands and lifting the lid. It is her thumb that wore the spot on the handle. For a moment, my Sita is present with me in my kitchen. I sit in my rocking chair to sip some morning tea. My bottom slides over the well-worn seat helping to erase the wood’s finish. The arms are worn as well. Rocking the chair back and forth, I remember the purchase of this chair from an Amish furniture store. It is the chair in which I rocked both of my babies to sleep each night. Worn as it is, I don’t care to have it refinished. I don’t want to disturb my memories of that tired mother or of those sleeping babies. On the wall adjacent to my rocking chair is a plate rack that contains four angel plates. Each white plate is decorated with the colorful image of an angel in a distinctive pose. One angel is ringing a bell, another holding a star. A third is playing a harp. The last angel is releasing a dove. The last plate was broken into several pieces during a move. I glued it together. On close inspection, the repair can be seen, but I don’t care. The plate stays. It is part of a set--a set of plates, and a set of friends. Some of my dearest friends, godparents to my children, gave me those plates on a Christmas day long ago. The plate rack was a find during an adventure with a new friend who has entered the ranks of dearest friends. I go to the storage cupboard for a box and spot a battered suitcase. It is very large. I never use it, but my baby girl, Emily, took it on a trip to Europe. She was in college and the first of our family to travel abroad. The suitcase still has the tags from her trip. Emily turned thirty this year, but I retain a piece of her youth in a suitcase in my closet. There are other scuffs, stains, cracks, and chips that fill my home—a child’s greasy hand prints, scuff marks from little feet. Blood stains from boo-boos. Chipped dishes from dropped spoons. I cherish all of these reminders of a life lived and of people loved. Scuffed, stained, cracked, or chipped, I want them IN. FOREVER.  In the years after my father separated from military service and moved us to the suburbs of Pittsburgh, I grew up and moved out on my own. I traveled to the city each day for work. While I was becoming a bonafide urban dweller, the world was changing. My small town roots were covered by the soil of a new reality. As a young child in the small village that was home to my extended family, I had roamed the streets without any fears. It wasn’t until I was a young adult and back for a visit at my aunt’s home that I lay my head down on the pillow one night and thought about the front door. There were sounds of angry voices coming from a bar down the street. Unsure of the cause of the racket, my senses went on alert, and for the first time in my life, I wondered if the doors to my aunt’s house were locked. Growing up, my regular territory was comprised mostly of the two main streets that made up the town. On each street there were open doors that I could walk into at any time. I didn’t have to knock or ring the bell. I did not need to phone ahead or wait for an invitation. My grandmother’s house was on Hanna Avenue, the center of our universe. Next door to her home was the family grocery store. My Aunt Addie lived on Main Street across from my Uncle Tony and Aunt Nancy. Many cousins filled the rooms of those houses. A short walk down Main Street and I was at the offices of the company my uncles owned and operated. The office was staffed by aunts and uncles and a few people who had worked for my uncles for so long, I thought they were my family. No one had security systems. Heck, they didn’t even have keys. If a doorbell rang, it really got our attention. These places were always open to me. I could step inside and use the bathroom, open the refrigerator, find good food and plenty of fun company. We were all one large pride. And then it happened. All the cubs grew up. The multitude of cousins slowly moved out and moved away. We joined the world of locks and keys, and later security systems. My cousins’ lives became busy and they had limited opportunities to return. Most of the time I was busy with my adult life too, but I returned to Hanna Avenue and Main Street whenever I could. Slowly, the aunts and uncles departed this world. Eventually, their houses were handed off to strangers, and I never again entered those doors. As a child, I thought that the whole world was made of houses like theirs, houses with open doors, homes jam-packed with aunts and uncles and cousins. I took it all for granted until it was no more. And then I began to feel like Puff the Magic Dragon after Jackie Paper grew up: “Puff no longer went to play along the Cherry Lane. Without his lifelong friend, Puff could not be brave…” It was easier for me to be brave on Hanna Avenue and Main Street. That is where the magic lived. But that is not the end of the story. Magic may sleep, but it does not die. Many years later, I moved to a new city. My daughter and I stepped into the check-out line in an unfamiliar grocery store. I took notice of the woman in front of me. “That looks like my cousin,” I said to my daughter. I tapped the woman on her shoulder, and she turned toward me. Presto-chango! It was my cousin. I no longer lived in a strange new city. I had kin! In the years since our meet-up in the grocery store, my cousin and I have weathered some significant family losses, moves and transitions. While we no longer live in a time when the doors are left unlocked all day and all night, I have my own keys and codes to her house. I have a new house with an open door. There is always good food and great company. From time to time, the dining room table is jam-packed full of cousins, and the aunts, uncles, and grandparents come back to us through the stories and the familiar voices and gestures that bubble up from our shared DNA. Life experience informs. The things we take for granted can be extraordinary. Magic can live in the ordinary. And each of us needs a house with an open door. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed