all of the selves we Have ever been

The children are gone. They grew up. Moved away. I face the compelling proof: there is no one to lick the spoon. I mix the thick batter and fold in the berries. And, just as I do each time I make this sweet bread, I briefly mourn the end of childhood in my home. Stirring the batter is a reckoning. I review the evidence: There are no toys in the bath tub. No scent of baby powder and shampoo. There is no car seat in the back of the car, no folding chair in the trunk. I do laundry twice a month now instead of twice a day. If the last piece of chocolate is missing, I know the culprit is me. There is never an empty roll of cardboard where the toilet paper should be. I no longer own a plunger. When I vacuum, there are no surprises underneath the couch. There is no one to wait up for, save for Jimmy Fallon or Stephen Colbert. The last of the outlet covers is gone. All of the scissors have long, sharp edges. There are no old purses filled with make believe. Barbie doesn’t live here any longer. No small voices vibrate my ear drums, I hear none of their special language: no “Blooty and the Beast,” no “comfyful.” I hear no jumping and singing behind the bathroom door. Nowhere is there the smell of sweaty heads or ripe gym clothes There is no artwork on the refrigerator door. No child snuggles in next to me when I read a book or watch a movie. The steady physical closeness, warmth, and affection, the frequent soft kisses, the holding of chubby hands—gone. A few weeks ago, I finished a book by Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere. It is a beautiful novel about two very different mothers and their children. One quote caught my attention, and I wrote it down: "Parents, she thought, learned to survive touching their children less and less…There had scarcely been a moment in the day when they had not been pressed together…It was like training yourself to live on the smell of an apple alone, when what you really wanted was to devour it, to sink your teeth into it and consume it, seeds, core, and all.” Perhaps, that is the great loss I mourn today as I use the spatula to wipe both the bowl and the spoon clean. I bake the bread and divide it into quarters. When the bread has cooled, I wrap each section. I put the pieces into the freezer for a day when the children come home for a visit, when, for a few moments, they are not gone. As I look ahead to that day, a soulful Alan Jackson song plays in my mind: "Remember when we said when we turned gray When the children grow up and move away We won’t be sad, we’ll be glad For all the life we’ve had And we’ll remember when” ************************************************************************************************ Blueberry Tea Cake 1 egg, beaten 2/3 cup sugar 1 ½ cups flour 2 teaspoons baking powder ½ teaspoon cinnamon ¾ teaspoon salt 1/3 cup milk 3 tablespoons butter, melted 1 teaspoon vanilla extract 1 cup fresh blueberries 2 tablespoons sugar

0 Comments

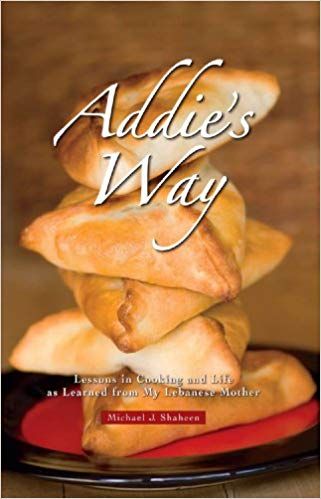

This pandemic is turning into an anatomy class. Remote learning--adult version. It started with two-for-one meat sales. Last week’s lesson was on butts. Which turned out to be shoulders. Today’s class is on legs. More precisely, thighs. And I haven’t seen this many thighs since 1965 when my parents took me to watch the Rockettes perform at Radio City Music Hall. Unfortunately, the thighs before me are all skin and bones. Intervention is needed. I call on the sharp and trusty tomato knife in the back row of my utensil drawer. As I work to de-skin and de-bone the chicken, my hands and the knife become coated in a thin layer of fat. Everything is slippery. I hope that I will not end up an amputee. The loss of some fingers would obliterate any financial gains from the two-for-one sale and certainly lead to a failing grade. My ancient cavewoman instinct is to grab the meat in my bare hands and tear it apart. I wrestle with this call of the wild and quickly triumph over my primitive urge. Though I am a modern, civilized, and educated woman, I only have so much self-control, and thus I limit myself to preparing just one package of thighs per day. As I work, I have a bird’s eye view of the upper leg, its structure and its strength. I picture a live hen--short, pencil-thin lower legs and chubby thighs, and I wonder: do chickens have knees? Is any part of a chicken’s leg called a calf? And why are poultry legs called drumsticks? The barnyard is rife for body image issues! This deep thinking leads me to ponder the preoccupation human females have with their own thighs. To understand that anatomy angst requires history, not science. I am pretty sure it all started with mini-skirts way back in the 1960s. Once hemlines began rising, a woman could no longer hide her long-leg girdle, garter belt, or her hamstrings. Pantyhose entered the picture, a temporary relief from the ties that bind, but they did little to conceal. The thighs were at constant risk of exposure. There would be no more bending at the waist. It was all knee action. If a woman forgot herself, it was gluteus maximus! If a really groovy gal decided to pair a mini skirt with some thigh high boots, she was trapped in a virtual body cast. A woman dressed in that combo could not bend at the waist or the knees. So, she might as well dance. Maybe she could get away with the Twist, Mashed Potato, Hitch Hike, or a cautious Funky Chicken. Crouching for the Monkey, or raising arms overhead for the Swim might put her moon as well as her thighs on display. You don’t have to be an astronomer to get the picture. Decades later, and just as women’s clothes were evolving into styles more comfortable and practical than the mini-dress, leggings hit the market followed quickly by their evil stepsisters, jeggings. To borrow one of my mother’s famous and colorful sayings, if you want to look like a stuffed sausage, try a pair. To say that leggings or jeggings cover your thighs is a mere legal technicality. If a woman wearing leggings has cellulite, we’ll know. Just sayin’… Now the evil sisters, leggings and jeggings, don’t just have it out for women, they like to trick their boyfriends by asking the loaded question, “Do I look fat in these?” Face it guys, you might as well drink poison. Perhaps that is what really happened to Romeo. Back in the days when women were obsessed with their waistlines and tight corsets, Juliet probably asked her beau, “Does this dress make me look fat?” Romeo took the bait. Juliet passed out from outrage and humiliation, and Romeo had no choice but to kill himself. Sorry, I’ve digressed from science to history to astronomy, and now we are talking Shakespeare. Meat sales really are an education! Somewhere between mini-skirts and leggings, there were tortuous exercises to achieve toned thighs. I don’t believe that is really possible, but women made Suzanne Somers rich by purchasing the Thigh Master. Or maybe it was the women’s husbands who were buying up the videos of Suzanne Somers doing the Thigh Master…That progressed to an obsession with the width of a woman’s thigh gap. Again, is a thigh gap even possible? But that is all to be dissected in the advanced class. I am still in Anatomy 101 and trying to find the answers to a few more basic questions: Why is a shoulder called a butt? And a leg called a drumstick? Do chickens have knees? And once I’ve mastered thighs, what’s next in the two-for-one meat aisle?  I tried a new recipe this morning. As I mixed condiments into a sauce to spread over some raw chicken, I began to doubt my choice of recipes. “Oh, geez! That looks like diarrhea,” I said. While not an enjoyable sensory experience, it did bring back a memory from my youth, and it made me smile. When my mother grew tired of her children’s complaints about “what’s for dinner,” she had a standard response for the next and last critic of the day. “What’s for dinner, Mom?” “Shit on a shingle.” “Mmm. Sounds good, Mom.” Enough questions asked. Suddenly, cabbage and Brussel sprouts didn’t sound so bad even if they smelled the same as the daily special. It was a master’s strategy. My mom was a well-educated, articulate microbiologist, not a mental health therapist, but she sure understood the power of crass language and visualization for changing minds and behaviors. Face it. Cooking for a family is hard work. Thinking about what to cook in order to please every taste is exhausting. However, children don’t know all of that. They are primitive pleasure-seekers with uneducated palates. They want what they want. It is easy to complain when a full meal appears on your table every evening. We were regularly reminded to eat what was on our plates and not be wasteful. “There are children starving in China,” our parents said. That was another master strategy–using guilt to gain compliance and elicit gratitude. My knowledge of China was limited to canned La Choy Chop Suey and the understanding that if I dug deep enough, I could tunnel my way to Asia. I thought my parents made up the story of those hungry children just to shut us up. Turns out children really were starving in China. While I was grudgingly choking down limp spinach, the Great Chinese Famine was taking 36 million lives. I guess that would have been far too much for a six year old to comprehend. It still seems unfathomable. Old-style parents weren’t about to explain themselves, or make six different meals, or fly in an order from a Michelin three-star restaurant in New York. There were limited prepared or processed foods in the house and, most certainly, no microwave to fix something special and quick for each picky eater. If visualization and guilt did not work, it boiled down to “Eat what’s on your plate…or else.” Going to bed without supper was an option in the parenting playbook, and we were smart enough to know that the “or else” chapter might contain scary mysteries we could imagine no better than a great famine. And so I plan to eat that chicken I made this morning--no matter what. Thankfully, it came out of the oven transformed--moist, browned and smelling delicious. Hopefully, I won’t be thinking of diarrhea when I dig in at dinner tonight. During this time of COVID-19, I employ the strategies from my parents’ old playbook. I take a bit of this and that from the refrigerator and craft a wholesome and delicious meal. I eat my sour-smelling vegetables, and I am grateful. The daily news reminds me that people in my own country as well as others around the world are going hungry. I don’t complain. I eat what is on my plate, and I do not waste food. I have not had to go to bed without supper. However, I do wonder what scary “or else” COVID-19 may be keeping from us. I pray there is a chapter in my parents’ old playbook that will see me through. Bon appetit!  The Ohio Governor is not hosting a news conference today. During this pandemic, my schedule of limited, stay-at-home activities centers on that daily 2:00 PM broadcast. Knowing there will be no update today, I realize I have an entire day off. What to do? The sun is shining. That’s a big plus. I open the window and a strong gust of wind pushes in like a busy toddler. It blows a coaster off a tabletop, turns back the cover of a magazine, and scatters a pile of papers onto the floor. I sit on the couch and try to read, but the lively breeze says, “PLAY!” Dull from spending so much time alone at my desk, I decide that I do need to MOVE. I reach a decision to initiate a new daily routine. I will go from room to room and tidy up all of the things I’ve been meaning to get to, but I will do it without any pressure or specific time table. I start with the kitchen. I open the first cabinet door and spy a dilapidated old two-pocket folder. The outside of the folder is decorated with images of the great baseballs stars of yesteryear. I think back to the day my son and I purchased this folder for a third grade class. The inside pockets are stuffed with recipes. Most are pages torn from old magazines, some are handwritten by me on pieces of scrap paper or sticky notes, and a few are in the neat handwriting of old friends. I study the familiar penmanship that brings the faces of these friends into view. I look at those recipes and remember the parties, the birthdays and the bridal showers that led to the sharing of the recipes. I remember how much I relish the sight of the distinctive handwriting of people I love. As I page through the contents of the folder, I notice that a number of the recipes were clipped from old magazines. Many are more than 40 years old. There are recipes saved from a time when I was a teenager dreaming of living on my own one day. I study the now dated product packaging pictured in the accompanying ads. It brings to mind another time and other kitchens. I see myself back there and remember the dreams I once had. Perhaps one of my dreams was to be a sculptor. My medium? Rice Krispies and marshmallows. There are several different sets of instructions for transforming the sticky goo into pink hearts with sprinkles, wreaths with gumdrops and licorice ribbons , stars on sticks, footballs, and little baskets. There is also a play-doh recipe that includes Kool-Aid as an ingredient. Ah, that dough occupied a lot of hours for me and for my children. Some recipes have no titles or identification. The instructions are incomplete. I have to study the notes hastily scrawled on sticky notes and bits of recycled paper and napkins. Oh, that one must be for turkey burgers. And here’s how to make a substitute for Worcestershire sauce which I rarely have. In the first pocket of the folder is a college-ruled notebook with a tattered red cover and rusted metal spiral. Inside are yellowed pages. My youthful handwriting is there in bright blue ink. I carefully turn the pages. I see recipes written in my own hand, recipes captured on a few rare days when I followed my Aunt Lillie or my Aunt Gen around the kitchen and recorded some of the family recipes they knew by heart. Some of the pages contain recipes copied from a favorite Good Housekeeping cookbook that was the master reference in my mother’s kitchen, the book that taught me how to cook. The notebook contains recipes for things once popular that I haven’t eaten or thought about in years. There are the cheese balls and liverwurst balls popular back in the day when my mom took her turn hosting card club. I remember the excitement of setting up those folding tables and chairs and laying out the spread of sophisticated adult snacks. I find the family recipe for grape leaves and Bishop’s Bread. Behind the notebook, my son’s favorite meal appears inside a plastic sleeve--chicken and cheese enchiladas. The ad says “M’m, M’m Good!” A little deeper in the pile is the chocolate mint brownie recipe that won my sixth grade daughter a blue ribbon in the annual Girl Scout bake-off. In the second pocket, right on top, is the must-have strawberry Jello dish that delights the extended family. We don’t know if it is a salad or a dessert, but it is a requirement at every gathering no matter the season. There is something so satisfying about the delicious blend of tart and sweet and salty, crunchy and creamy. I look forward to making this once again when my family gathers to celebrate the end of the pandemic. I review each page, each sticky note, each napkin. I clip the rough edges and smooth out the wrinkles. I place each recipe in a protective plastic sleeve and organize it all into a binder. I give those recipes the honor they deserve for their lifetime of service. I tuck a note inside that that says, “These recipes were lovingly reviewed, collected and preserved on March 29th during the great COVID-19 epidemic of 2020.” This binder contains not just recipes, but important history. And now it is a gift to the future, for a time when my children and grandchildren get hungry, hungry for their youth, hungry for the old days, and hungry for me.  Dear Friends, I have written about the loss of my Sita’s raisin bread recipe. Some of you have asked about the other foods she prepared in her kitchen. Many of those recipes were collected by one of Sita’s daughters, my Aunt Addie. Initially, Addie published the recipes as a small, spiral-bound cookbook titled Feast from Famine which was distributed to members of the extended family. Aunt Addie was a remarkable cook in her own right, and after her death, her son, another of Sita’s grandchildren, Michael Shaheen, created a beautiful cookbook and food memoir titled Addie’s Way. In addition to the recipes, Addie’s Way displays the gorgeous professional photography of another of Sita’s grandchildren, my cousin Nannette Bedway. Food has never looked so good! Addie’s Way by Michael Shaheen is available for purchase on Amazon.com. Now, I ask that you please bear with me as I pen a quick note to my Sita: Dear Sita Your recipes are going out into the world, to places far from the small village where you knew everyone’s name and every crack in the sidewalk between your house and the church. Your food provided sustenance for our bodies and your example, nourishment for our lives. We can never know the extent of the suffering that brought you to this country. We know that the journey was not easy, that you suffered more on route and in the years that followed. And still, you were a model of faith, determination, kindness, generosity, and gratitude. I hope that you can see us now. You did well! May all of our lives reflect the hope that was in your heart that momentous day when you bravely set sail for a brand new world. With love and gratitude, Lilli-ann  My Sita My Sita I have tasted love. In the time before Food Network and TV chefs, long before “foodie” was a word, there were meat-roasting, soup-simmering, cookie-making, bread-baking grandmothers. My maternal grandmother, my Sita, immigrated to this country from Lebanon when she was a young woman. Unable to speak English, Sita found her voice in the kitchen. My grandmother articulated her love for us through the language of food. The table became the canvas upon which she displayed her artistry. Sita possessed a magic that could turn the simplest ingredients such as rice or lentils into delicious, exotic fare. “Food in proportion to the love,” was Sita’s motto. Neither stomachs nor souls went hungry in our grandmother’s house. For me, Sita’s masterpiece was her raisin bread. Excitement stirred in the kitchen when raisin bread was in the making. Assisted by one or more of her seven daughters, Sita mixed the ingredients in a large wooden bowl. Soon sweet, slightly sticky dough dotted with dark raisins emerged much to the delight of her grandchildren. Just before Sita covered the dough with her old navy blue sweater, she would give my sister and me each a small ball of the sweet, stretchy paste. Sita told us that we could play with the dough, but we should not eat it. Out the back door and onto the porch we went. Occasionally, my sister or I tossed one of the little balls into the air and caught it so Sita could see from the window that we were indeed just playing with the dough. In fact, we were nibbling away. I don’t recall the explanations we gave when our rations were consumed, but the taste and pleasure were worth any consequence. As I grew older, I realized that Sita had given us the dough to keep us quiet while the bread dough was rising, but our young selves thought we were helping, and we were eager and proud to be part of the special occasion. After Sita died, my Aunt Lillie took to making the raisin bread just the way Sita had—same wooden bowl, same recipe, the ingredients for which were recorded only on her heart. Old enough by then, my sister and I served as our Aunt’s actual assistants in the bread-making effort. After the dough was kneaded and placed back into the bowl to rise, Aunt Lillie would send one of us to retrieve the same thin navy blue sweater our Sita had worn and used to cover the dough. As Aunt Lillie lay that old sweater across the dough-filled bowl, she would say, “And now for the love part.” After my Aunt Lillie died, the bread making stopped. The recipe went with her. Where the sweater went I do not know, but a portion of the love that filled the sweater that covered the dough is now inside of me. More than fifty years have passed since I first stood alongside my Sita in her bright yellow kitchen eagerly awaiting my ration of that delicious dough. Her house is gone along with the recipe. Despite the many efforts of daughters and nieces, no one has been able to replicate the exact formula for our Sita’s raisin bread, but food continues to be a centerpiece in our lives—it is a reason to gather, a source of strength, a medicine and a comfort, an offering of love in large proportions. It is around our tables that we celebrate all of the selves we have ever been and the ones from whom we came. So, here is to grandmothers and to all of us who ate the bread, tasted the love, and who remember. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed