all of the selves we Have ever been

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine suffered sudden heart failure while dining out at a local restaurant. It happened just before the peanut butter pie was served. In what can only be explained as divine intervention, a physician, a navy medic, and a retired cardiac-care nurse were also dining at separate tables in the restaurant. They came to my friend’s aid. In their frantic life-saving efforts, a couple of my friend’s ribs were broken. That was a small price to pay for restoring life to this happy, much-loved, vital woman just a few days short of her 45th birthday. My friend later learned that the restaurant patrons gathered in a circle to pray as the emergency squad drove her away to a nearby hospital. Everyone was shaken. And moved. It is a powerful thing to watch life leave a person, and it is an equally powerful thing to recognize the awesome power in our hands to restore life, to feel the formidable responsibility for the ongoing existence of another human being, to see our hands as life-giving tools--a spark of the divine in each of us. In this time of growing hatred in which too many people are preoccupied with sucking the life out of each other, it is inspiring to learn of a situation in which good hearts responded without hesitation to breathe life into a stranger. It did not matter my friend's political persuasions. All any one needed to know was that she was in trouble and every second mattered. It was a heart-to-heart decision. Humanity and decency prevailed. When there is no one to mock us or create doubt in us, our good hearts are stirred to do the right thing because life matters--to us and to each other. My friend received outstanding cardiac care at the hospital. Chalk one up for science! She is now the recipient of an implanted defibrillator that will provide electric current to power her good heart should it ever again go out of rhythm. I think we could all use a defibrillator to shock us now and then, restore our good hearts when they are out of whack. Plug us in. Bring back this transformative power to the people. May the beat go on.

2 Comments

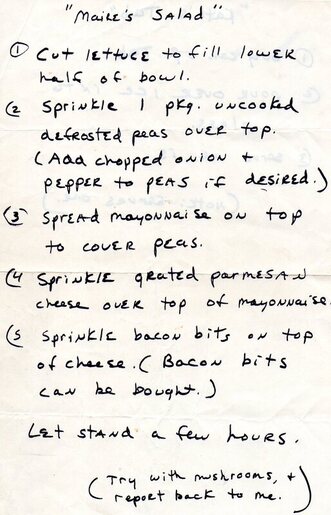

I had not felt well for several days. Sick of feeling miserable I got it into my head that the cure was Cheetos, but I had none. I learned long ago the dangers of keeping snack foods in the house, and so I never do. But as I said, I got it into my head that the cure for my malaise was Cheetos, extra crunchy. So, in the middle of a thunderstorm, I got into my car and headed for the nearest convenience store. Of course, there were no snack-size bags available. It would be the share-size or nothing. The first warning bell rang. Despite the sounding alarm, I did not run for the door. I stood there studying the image of the skateboarding cheetah in sunglasses. He looked happy with a giant Cheeto in his hand. His white high-top sneakers looked lovely too, and I couldn’t help but notice that he was quite slender, undernourished even, for a carnivore. Maybe Cheetos are a health food. I was easy prey, and I grabbed a bag. I approached the check-out feeling like a teenager about to get an overhead price check on tampons or condoms, but there was no cashier behind the counter. The second warning bell chimed. For an instant, I pondered the possibility that God was giving me another chance to make a better decision. I set the bag of Cheetos on the counter as I waited for the cashier. Though it was inadvertent, I had remarkable precision in aiming the price code at the resting scanner. The cash register began ringing up the Cheetos over and over again. Strike three and red alert! God was going rounds with the devil. The cashier came running to the register from some unseen location behind me. It was too late now. The devil had gained the advantage. Now, I had to buy the Cheetos. As the young lady deleted the repeated charges and started to tally my actual purchase, I felt compelled to explain that I don’t usually eat such foods. “Mm-hmm.” I could see that she didn’t care one bit about my dietary habits or if I was telling the truth. She worked in a convenience store, for God’s sake, the devil’s outpost. She wasn’t there to hear confession. I grabbed my purchase from the counter and dodged hail on my way back to the car. Alone inside my vehicle I tore open the package. Lightening flashed as I glanced at the calories per serving printed on the bag. Why did I do that? Now I knew the cost of sin. I set about negotiating. I vowed I would eat just one serving. And then I vowed that if I ate more than one serving, I would balance out the calories throughout the rest of the day. And then I vowed just to make it home. I showed amazing restraint in the car. I ate just one Cheeto. I have to admit that it was pretty darn good. And then I made it all the way into the house. With each Cheeto I consumed, I renegotiated the serving size. Pretty soon, I did feel better. How many Cheetos did it take to cure my ills? I’m not saying, but it was enough to leave a big orange stain on my soul.  I burned my cheek with a curling iron. Two days later, the area below my left eye had swollen into a squishy lump the size of a baseball. Despite the pound of flesh, my hair still looked like hell. Of course, this happened on a Friday. There were no appointments available at my doctor’s office. I made two attempts at nearby walk-in clinics. On the first attempt, everyone was out to lunch. By the second attempt, the clinic schedule was booked for the rest of the day. Employing the three-strike rule, I went back to the bench. By then, the day was pushing into evening. I weighed my odds: the wound would either get better or worse. If it got better, I would save time and money. If it got worse, I would spend a large portion of the weekend and my 401(k) in the emergency room. I placed my bet on good hygiene and “a tincture of time” as one of my former general practitioners used to say, and I went to the medicine cabinet. After reviewing my arsenal, I selected hydrogen peroxide to cleanse the wound and antibiotic ointment to treat it. These measures did not stop me from obsessively combing the internet instead of attending to my unruly hair. I spent a long, restless night convinced I would die from tetanus. Morning came, and I lived—a small victory for benchwarmers everywhere. When we were kids, we suffered our injuries and left the sleepless nights to our parents. Back then, I would have slathered the burn with butter and got on with my day. If that wasn’t enough intervention, I would have retired to the couch with a soft striped afghan and an afternoon of cartoons. If my mother felt some sympathy for me, she might have brought me warm tea and cinnamon toast. If the situation escalated, the family doctor would have been consulted by phone or stopped by for a late evening house call. The family physician’s entire arsenal fit into a little black medical bag, a supplement to the basics we all had at home. Home medicine cabinets contained far fewer germ-fighting, cough-suppressing, pain-relieving, age-reversing weapons than we have now. The first-aid kit of my youth contained a mercury thermometer, baby aspirin, and Mercurochrome. With luck, there might be a Band-Aid to spare if Chatty Cathy had not suffered a boo-boo while we were playing house. Most other healing agents were found in the kitchen: baking soda, a shot of whiskey, hot tea, honey, chicken soup, cinnamon toast, and butter. Butter was certainly handy in the kitchen where most minor burns occurred, but I discovered that modern internet sites do not recommend butter as a treatment for burns because it traps in the heat and has no antibiotic properties. The exception to the no-butter-to-the-burn rule is when removing hot tar from human flesh. I will keep that in mind in case I prove to be a worse roofer than I am a hair stylist. In any case, I am happy to have a reason to keep butter around in the enlightened age. Mercury-containing products were quietly escorted off the drug store shelves a long time ago, but my knees are permanently pink from Mercurochrome. I may have experienced brain damage from the mercury-laced antiseptic and from chasing those little beads of mercury around the kitchen floor when a thermometer broke. With all of that accumulated mercury and the trapped heat from so much butter, it is no wonder that I am a woman on fire. I now understand menopause and the stir-fried condition of my hair. There was a time when health enthusiasts and food manufacturers tried to convince us that a new product, oleomargarine, was better for us than butter. I think the shift may have started during the mercury years. Eventually, margarine went the way of mercury. It proved to be worse for our health than butter. Let’s face it, butter has staying power. From well-stocked grocery store aisles to ample, soft hips, no amount of fat-shaming or internet advice can turn us against butter. Speaking for myself, I can stand up to the saturated fat in beef and bacon. I eat those meats about as often as I attend a high school reunion. I am willing to remove the slimy skin and fat from chicken which is my diet’s protein mainstay, but the butter stays. I honor it by keeping it an old dish that belonged to my grandmother. I might portion it out in teaspoons like a heroin addict, but I don’t even pretend that I will give it up “tomorrow.” I don’t need to read a recipe or to perform a chemical analysis to know if a dish contains butter. If the food is delicious, it contains butter. Quite frankly, I am astonished that butter does not require a prescription. Is it possible to be anxious or depressed while eating a soft, chewy brownie? How about the high that comes with eating a flaky, buttery biscuit? I am willing to live with the side effects. After feeling the burn, my advice is to get a tetanus booster and a good haircut. Don’t put butter on your burns. Save the butter for the big stuff, the internal injuries—damaged egos and broken hearts. In the event of catastrophic injury, increase the dose and add a scoop of ice cream. If I am wrong about this advice, don’t blame me; it might be the mercury talking.  I knew them both. A few short miles separated their houses. A greater distance separated their lives. He had everything, it seemed. She had nothing. Their ages differed by more than fifty years. He had passed the age of ninety. She was barely thirty-five. A wide gulf separated their achievements. He was a decorated soldier, a retired corporate executive, and a practicing lay minister. She worked in a hotel, making beds and scrubbing toilets. He created a family that spanned many generations, and he had lived to see the children of his great-grandchildren. She would not live to see her only child go off to kindergarten. His stately home was built of brick and sat beaming on a cul-de-sac in an old, established neighborhood. A yard sign advertised his house on the Holiday Tour of Homes. In the garage, a boat kept company with a luxury automobile. His home was paid for. He had money in the bank and two hefty pensions. He lived each day surrounded by tasteful furnishings and expensive collectibles. She lived in a modest tract home in a low-rent neighborhood where broken-down vehicles lined the streets. A security camera on the house next door blinked the steady reminder of a break-in. Her small Ford was parked in the driveway, but it really belonged to the bank, not to her. She had no savings. Bill collectors called. She hoped to receive a disability check. Holes from a man’s fist, holes from her head accented the walls. He had the pleasure of a marriage that lasted more than fifty years. He said his wife was his closest friend. She awaited the arrival of a divorce decree. She said she still loved the man who put the holes in the walls. Despite his training and ministry to others, he believed that God was a son-of-a-bitch with a bad sense of humor. She had no religious instruction but hoped that God was kind and watching over her. He had many well-educated and capable adult children who tried to care for him, but he chased them away with his irascible disposition. With grace and patience, she allowed a mentally ill mother and a drug-addicted sister to care for her, to rise above their means and their own problems, to be better and braver than they might otherwise be. He greeted every day with contempt and hostility. He behaved so badly that a sigh of relief was offered to heaven when he passed suddenly and alone. She was surprised and grateful to open her eyes each day. She was showered with attention, tender care, and kisses. Heaven’s gate opened wide to a woman loved. Appearances can be deceiving. He that dies with the most toys is not always the winner. In the end, when both had died just days apart, she was the one who had everything.  “A thundering velvet hand...” “A gentle means of sculpting souls” Those are the words that Dan Fogelberg used to describe his father, a school band director. After the song, Leader of the Band, became a hit, Fogelberg said in an interview that if he had written only one song, Leader of the Band would be it. His father was surely someone remarkable and loved. Another singer-songwriter, Bill Withers, wrote and sang about the hands of his maternal grandmother, Lula Galloway, with whom Withers attended church on Sunday mornings. Lula used those gnarled hands to clap and sing in church and to protect and nurture her grandson. Withers wrote “Grandma's hands picked me up each time I fell…If I get to heaven I’ll look for Grandma’s hands.” We are each born with our lives in someone else’s hands. Throughout life, we rely on safe hands. Kind hands. Gentle hands. We remember the helping hands. In our family, we are all thumbs. When my son Sam was a toddler, we had a bedtime routine. I would lie down beside him for a few minutes as he settled into sleep. Sam would wrap his chubby little hand around my thumb, and I would sing as he fell asleep. At bedtime one busy evening, I was unable to stop what I was doing in order to get Sam to bed. My daughter Emily, Sam’s sweet and earnest big sister by three years, said, “I’ll lay down with you, Sam. You can hold my thumb.” Sam shook his head. “No, Em-a-wee. I need a BIG fum.” I understand. I had a big “fum” when I was a child. That big thumb was attached to the right hand of my Uncle John. He was not a band leader, but Uncle John did have one of those thundering velvet hands. He was a gentle soul and a giant in my life story. He deserves his own song. Uncle John made it his mission to shape the souls of a huge tribe of nieces and nephews in addition to those of his own five children. I don’t know how it began or why, but whenever Uncle John came into our presence, he extended his hand, “Touch thumbs,” he would say, and our little fums shot up, and we made contact. It was a safe and convenient display of affection, especially when Uncle John was in the driver’s seat transporting a station wagon full of squirming children to the swimming pool or the custard stand. Before he started the engine, Uncle John would turn to face us, extend his right hand, thumb up, and each of us would jockey to reach him and touch our thumb to his. The journey did not begin until each of us had made contact. Towel? Check. Sunscreen? Check. Seen and loved? Check. Check. Sometimes on a Sunday morning, Uncle John would slide into the church pew next to me. He might reach out his thumb or wrap his hand around mine. Once in a while his hand would slip a silver or gold bracelet into my pocket. Often when we parted, Uncle John would slip a twenty dollar bill into the palm of each of the gathered nieces and nephews. He continued the tradition long after we all became working adults. Nothing escaped Uncle John’s view, but he never used those hands to “stir the pot,” an amazing accomplishment in a large and highly emotional extended family with enough teenagers for plenty of trouble. Touching thumbs was an act that never got old or lost its power. When my daughter Emily was born, a C-section turned to near-disaster with a life-threatening hemorrhage. After a touch-and-go stay in the intensive care unit, I was sent to a regular room on the obstetrics unit. Just settled in my bed still surrounded by IV poles, so full of fluid I could not blink my eyes or bend my knees, I turned my head to the left, and there was my Uncle John and his wife Aunt Janet. Upon seeing them, I began to weep. All of the terror and exhaustion of the past few days came bursting out of me. They came to the bedside. Uncle John’s jaw was tense, his lips tight and twitching at the right corner as he blinked away his own tears. He reached for my left hand and touched my thumb with his. We were frozen in a moment of terrifying what-could-have-been and then relief. The healing power of big fums! Many years later, I would stand in an intensive care unit alongside the bed of my cousin Marcia, Uncle John’s baby girl. A heart catheterization turned disaster. Marcia did not open her eyes. As the ICU nurse sorted the tubes and monitored the equipment, I wanted the nurse to know that this woman, our Marcia, was someone special. I told the nurse about Marcia’s life and accomplishments, and then I touched Marcia’s left thumb with mine. By morning, Marcia was gone. When it is my turn, and I get to heaven, I’ll look for those hands. I will know them by their thumbs.  Maire was the last of my other-mothers. She entered my life when I was a young adult in my early working years. Maire was the mother of my friend Kathy. Kathy was new to Pittsburgh. At the end of a long work day, a fortuitous meeting on a city bus delivered Kathy and me to our adjacent apartment buildings and to a lifetime of wonderful friendship. We both worked in the same downtown office building and so shared office gossip and that long ride home. We also shared the same quirky sense of humor. As our friendship evolved, it didn’t take much to have us both falling over with laughter from jokes no one else understood. We vacationed together at the ocean. Having heard from others that the most surefire way to destroy a friendship is to travel together, Kathy and I talked about our plans. “As long as you don’t make me learn anything, I’m in,” Kathy said. And so, the word “relax” became our mission and our motto. And we were really good at it. Still are. From time to time, Kathy invited me to accompany her for the five hour drive to her parents’ home in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It was a beautiful home of modern design in the heart of Amish country. The blend of modern and traditional described Kathy’s parents as well as their home. Maire was a working woman, interested in style and current trends, but she was also a master of the home arts, maintaining a lovely décor, quilting, and cooking up delicious corn chowder. If hospitality is, indeed, a form of worship, than Maire’s home was a church. When Kathy’s parents visited her in Pittsburgh, I was often invited to join them. Sometimes the three of us gals would go shopping. Kathy and I could find plenty to bring us to fits of laughter. Maire’s puzzled looks indicated that she did not always get the reason for so much hysteria, but she was patient and never admonished us with more than an “Oh, you girls!” During eleven of the years that I knew Maire, she faced down five primary cancers. These were not minor episodes. Cancer invaded her breasts. It was the same cancer that had taken the lives of other women in her family. The cancer turned up again in her hip and then returned to occupy other organs. The treatments were long and painful. Throughout it all, Maire remained positive and determined. If she read an article that suggested eating five almonds a day was good for your health, then Maire made it a habit to eat five almonds a day and to encourage us to do the same. If she read about a new wellness community popping up somewhere in the country, she boarded the plane. Many years into her lengthy battles with cancer, I experienced a life-threatening medical emergency of my own, one that took me to the other side and brought me back. During my recovery at home, Maire phoned in a show of support. We chatted a bit about life, in general, and then Maire asked more specifically about my health and physical recovery. I had already learned that most people do not want to hear the painful details, but Maire encouraged me to talk openly about my experience. Then she said something that flabbergasted me: “Isn’t the hardest part the mental part?” I was stunned. Throughout all of her diagnoses, surgeries, treatments and periods of recovery, I never imagined that Maire went through “the mental part” that I was going through at the time. Maire had always seemed so accepting, so positive. As I inched forward in my own recovery, it did not occur to me that my suffering was the suffering of all who experience such brutal assaults on health and life. The mental part is the part that no one sees, and it is the most exhausting and debilitating part of illness. It is the cause of the great loneliness of being a patient. No matter how much love surrounds, no matter how many hands pitch in, recovery is about garnering the strength to climb out of the hole. No one can do it for you. You are alone. I did not realize Maire had been like me—waking up each morning feeling weak and terrible, checking for the signs that you are still alive. Then beginning the bargaining: “Please, God, let me make it to the toilet on my own.” On the toilet, the next round begins, “Please, God, let me make it back to my bed.” Then the next, “Please, let me keep down some food today.” Coaxing yourself: “Just one more bite,” or “Just one more step.” And on..and on..all day…every day…exhausting negotiations with God and with yourself. Maire’s words were like medicine to me. To know that this woman I so admired had survived the same dark hole, had entered into the same lengthy and daily negotiations was the revelation I needed to know that I could survive this too. I am sure I was not so classy as Maire, but she had thrown me a lifeline, an example of how it could be done. I trusted her, and I could hang on. Maire died a few years later. I have a fabric square from a quilt she started for my baby girl, a piece of her jewelry, and one of her cookbooks. Best of all, I have her own baby girl as my friend. Our shared memories of Maire will eternally cement our friendship. Maire was my other-mother. Along with the necklace and the recipes, I hope I inherited a portion of her tremendous strength and grace. And I hope that I can be as honest and as brave as Maire when someone else needs a lifeline, when the mental part becomes too hard. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed