all of the selves we Have ever been

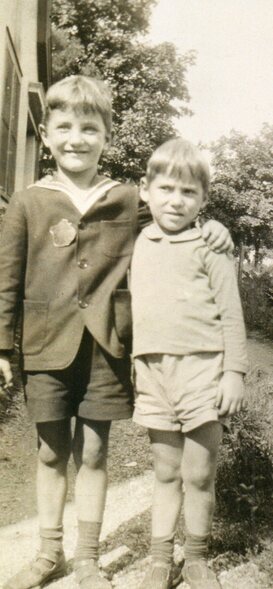

My father’s pack was already heavy that day that he enlisted in the United States Army. He just didn’t know it yet. At 16, filled with youthful energy and resolve, dad thought he had found a solution to life’s problems. His father died when dad was 14. The death was sudden and unexpected—a bad case of pneumonia before the advent of antibiotics. It did not take long for the pneumonia to overtake my grandfather. In a couple of days, he went from being a healthy, active dad of two boys to only a memory. The older of the two boys and now responsible for the care of his disabled mother and little brother, dad made a pact with his brother Bob. As soon as he could, dad would enlist in the military and provide financially for their needs. Bob would remain at home and care for their mother. Already in that invisible pack the day dad enlisted: being born at the start of the Great Depression to two physically disabled parents; living on the edge of poverty throughout his youth; a great war that terrified the world and made the future uncertain; the death of a father and no time to mourn; worry and care for a younger sibling and a grieving mother. Added to that pack through years of military service first in the Army and then the Air Force: adjustment to military life, a pack or two of cigarettes each day; a hasty and short marriage that ended in annulment; deployments; marriage and four children; moving every couple of years; job stress; deaths of family members. It seemed the pack was bottomless. After 17 years of active duty, my father separated from the military. Later, my parents divorced, and my father moved away. More weight for the pack. Further down the road, he developed pancreatic cancer. Dad faced it like a soldier-airman, and through a miracle that awed his doctors, dad lived five more years. The illness and treatment took a toll, but dad had some quality of life. Disappointed that he no longer had the stamina to work, dad became a hospice volunteer. My talented and artistic sister-in-law made dad some calling cards that said, “Believe in Miracles.” Dad was a hit in his hospice circle. When our father’s cancer returned, his attempts at treatment were halfhearted. My brother, HB, became desperate to keep our father alive. HB had a menu of health drinks that he concocted daily for Dad. During a visit to his home, I noticed that Dad left the health potions untouched on the end table while he stared blankly at the TV. One day, alone with my father, I pointed out the warm health drink that now looked thick, flat and disgusting. “Dad, you don’t want to do this, do you?” My father began to cry. He had nothing left, he said. The first round of cancer had been so difficult that it took everything he had to survive. “We must tell the others,” I said. True to his roots as a soldier and an airman, my father expressed a feeling of shame about giving up. He did not want any of us to be disappointed in him. He did not want to let us down. I assured him that we all understood. We had all been with dad through that first horrifying round of surgeries, complications, and treatments. We had all survived dad’s blackout and car crash that sent us searching for him in the night when his blood sugar tanked as he tried to adjust to his post-surgical insulin-dependence. As the disease progressed, I often spoke to my father by phone—he from his home in California, me from my home in Ohio. I always knew it was dad calling because I heard gut-wrenching sobs coming from the other end of the line when I answered the phone. I waited patiently until my father reached the point where he had exhausted himself and could cry no more. I then offered what comfort I could. One day the phone rang. Again, there was sobbing on the other end of the line. When the sobbing ceased, and it was quiet, I spoke, “Dad, I know that you are sick and sad and scared, but somehow I know there is something more that you are not saying.” More tears. “For fifty hears something has been bugging me. Until now, I never knew what it was.” The thing that had been bugging my father for most of his life was the death of his own father. Years of unexpressed grief were now overtaking my dad. “Because of it, I was not the man I could have been. I was not the father I wanted to be. I did not have the life I dreamed of.” Dad’s last piece of fatherly advice: “Don’t let sorrow ruin your life.” In that moment on the phone, Dad’s invisible pack burst open. There was no holding it back. The pack had grown so enormous and so heavy that the real man had been hidden from view. It had gotten in the way of fully living his life. My father was like Sisyphus rolling a giant boulder up the mountain. Every day was consumed by the effort of shouldering his invisible pack. And now he had insight but no time left for a do-over. Mercifully, there was enough time for frank conversations and forgiveness. Dad grew up in a time when people did not talk openly about their sorrows. Adults did not even believe that children were affected by events like the death of a parent. My father reached manhood amongst the brave but silent World War II veterans who provided an example of how to be a soldier and a man. We all come into this world with an invisible pack. Some of us are fortunate to reach adulthood with little weight added. Others, like my dad, carry overwhelming burdens before they reach high school. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote: “Sorrow makes us all children again…” For my father, the overwhelming sorrow of childhood robbed him of a successful adulthood. Though handsome in his uniform, It was all dress-up and make believe. Dad’s pack was heavy. It weighed on all of us. We just didn’t know it. The commercial airlines have it right. Keep your baggage light or it may cost you more than you want to pay.

3 Comments

Such a beautifully written and powerful essay. Such a pack was first strapped on your father's back by a culture that kept men from expressing the full range of emotion that comes with being human. Bless him for being able, finally, to weep to the daughter who could bear it with him.

Reply

Justin Secrest

2/22/2020 04:05:12 pm

Such great writing! So moving—so true Keep your pack light or you pay a high price. I suppose we don’t get to chose what goes in, but we can chose to move heavy things out.

Reply

Reylene Gard

3/7/2020 07:03:53 am

Such a beautifully written story. I am in tears as I write this. So many thoughts of my own story going on in my head. Both my parents grew up in a time that did not allow them to share their feelings. Sadly they both died without me ever really knowing their stories. Thank you for sharing your stories.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorLilli-ann Buffin Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed